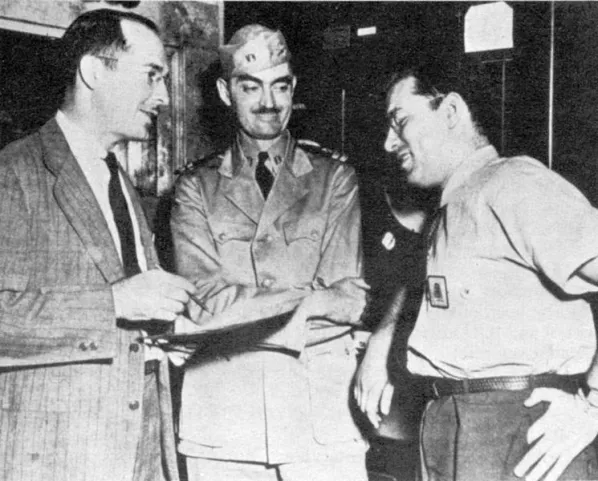

Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov and L. Sprague De Camp at the Navy Yard in 1944

Robert Heinlein was born in 1907, which put him on the mature side by the time of the United States’ entry into World War II. Isaac Asimov, his younger colleague in science fiction, was born in 1920 (or thereabouts), and thus of prime fighting age. But in the event, they made most of their contribution to the war effort in the same place, the Naval Aviation Experimental Station in Philadelphia. By 1942, Heinlein had become the preeminent sci-fi writer in America, and the 22-year-old Asimov, a graduate student in chemistry at Columbia, had already made a name for himself in the field. It was Heinlein, who’d signed on to run a materials testing laboratory at the Yard, who brought Asimov into the military-research fold.

Having once been a Navy officer, discharged due to tuberculosis, Heinlein jumped at the chance to serve his country once again. During World War II, writes John Redford at A Niche in the Library of Babel, “his most direct contribution was in discussions of how to merge data from sonar, radar, and visual sightings with his friend Cal Laning, who captained a destroyer in the Pacific and was later a rear admiral. Laning used those ideas to good effect in the Battle of Leyte Gulf in 1944, the largest naval battle ever fought.” Asimov “was mainly involved in testing materials,” including those used to make “dye markers for airmen downed at sea. These were tubes of fluorescent chemicals that would form a big green patch on the water around the guy in his life jacket. The patch could be seen by searching aircraft.”

Asimov scholars should note that a test of those dye markers counts as one of just two occasions in his life that the aerophobic writer ever dared to fly. That may well have been the most harrowing of either his or Heinlein’s wartime experiences, they were both involved in the suitably speculative “Kamikaze Group,” which was meant to work on “invisibility, death rays, force fields, weather control” — or so Paul Malmont tells it in his novel The Astounding, the Amazing, and the Unknown. You can read a less heightened account of Heinlein and Asimov’s war in Astounding, Alec Nevala-Lee’s history of American science fiction.

Their time together in Philadephia wasn’t long. “As the war ended, Asimov was drafted into the Army, where he spent nine months before he was able to leave, where he returned to his studies and writing,” according to Andrew Liptak at Kirkus Reviews. “Heinlein contemplated returning to writing full time, as a viable career, rather than as a side exercise.” When he left the Naval Aviation Experimental Station, “he resumed writing and working on placing stories in magazines.” In the decades thereafter, Heinlein’s work took on an increasingly militaristic sensibility, and Asimov’s became more and more concerned with the enterprise of human civilization broadly speaking. But pinning down the influence of their war on their work is an exercise best left to the sci-fi scholars.

Related content:

Sci-Fi Icon Robert Heinlein Lists 5 Essential Rules for Making a Living as a Writer

Isaac Asimov Recalls the Golden Age of Science Fiction (1937–1950)

Sci-Fi Writer Robert Heinlein Imagines the Year 2000 in 1949, and Gets it Mostly Wrong

X Minus One: Hear Classic Sci-Fi Radio Stories from Asimov, Heinlein, Bradbury & Dick

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: 17,500 Entries on All Things Sci-Fi Are Now Free Online

Read Hundreds of Free Sci-Fi Stories from Asimov, Lovecraft, Bradbury, Dick, Clarke & More

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.