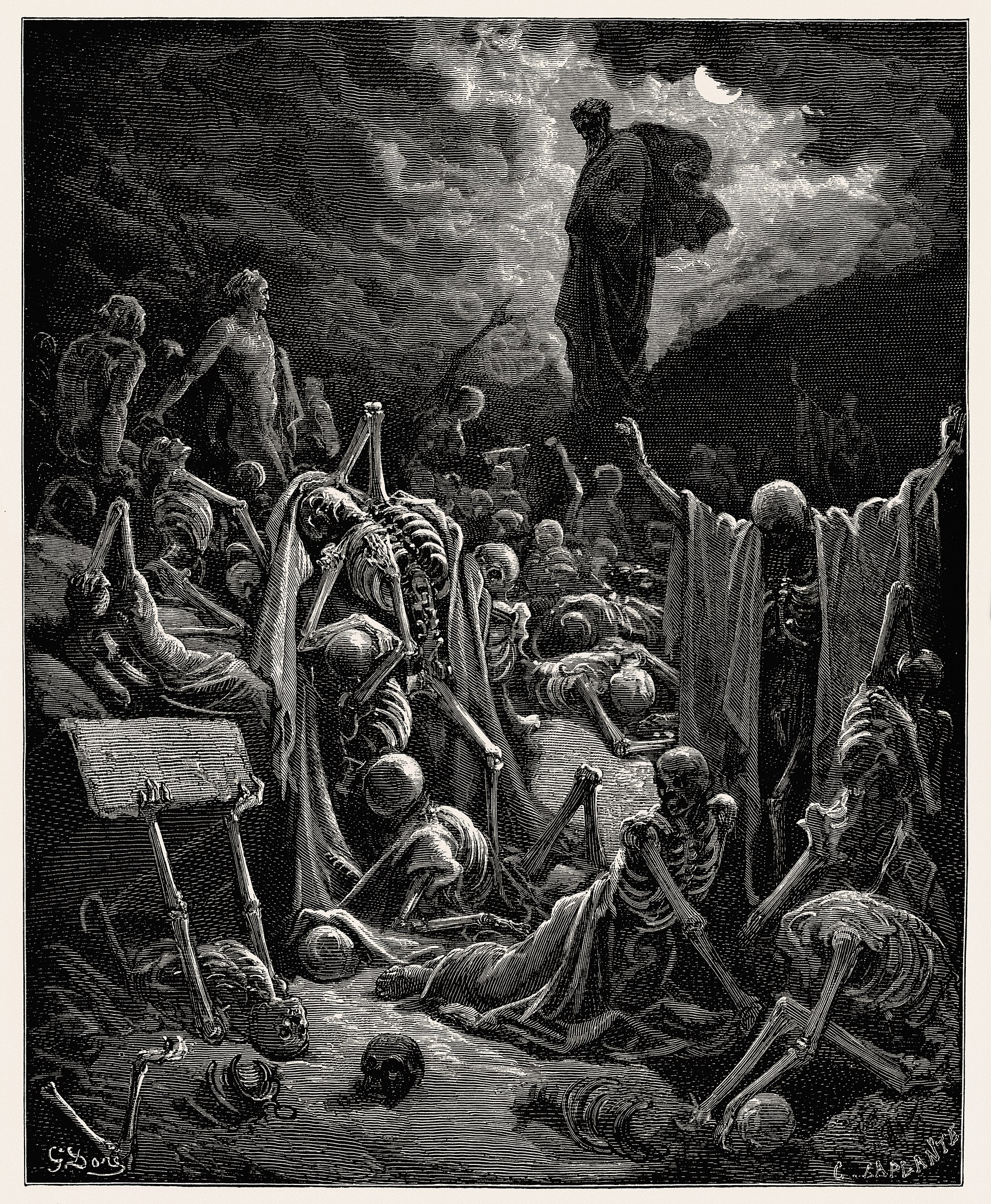

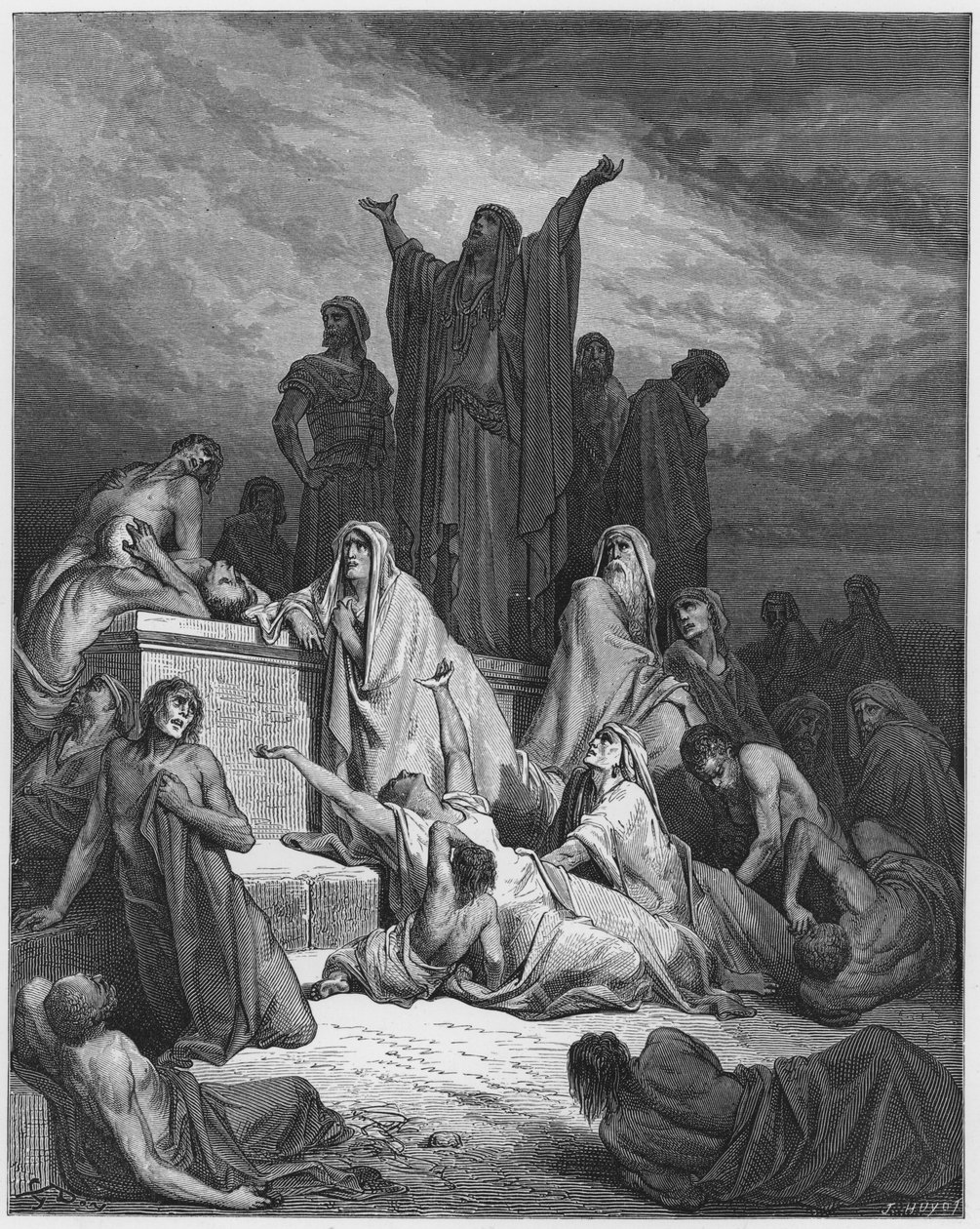

One occasionally hears it said that, thanks to the internet, all the books truly worth reading are free: Shakespeare, Don Quixote, the stories of Edgar Allan Poe, the Divine Comedy, the Bible. Can it be a coincidence that all of these works inspired illustrations by Gustave Doré? When he was active in mid-nineteenth-century France, he worked in a variety of forms, including painting, sculpture, and even comics and caricatures. But he lives on through nothing so much as his woodblock-print illustrations of what we now consider classics of Western literature — and, in the case of La Grande Bible de Tours, a text we could describe as “super-canonical.”

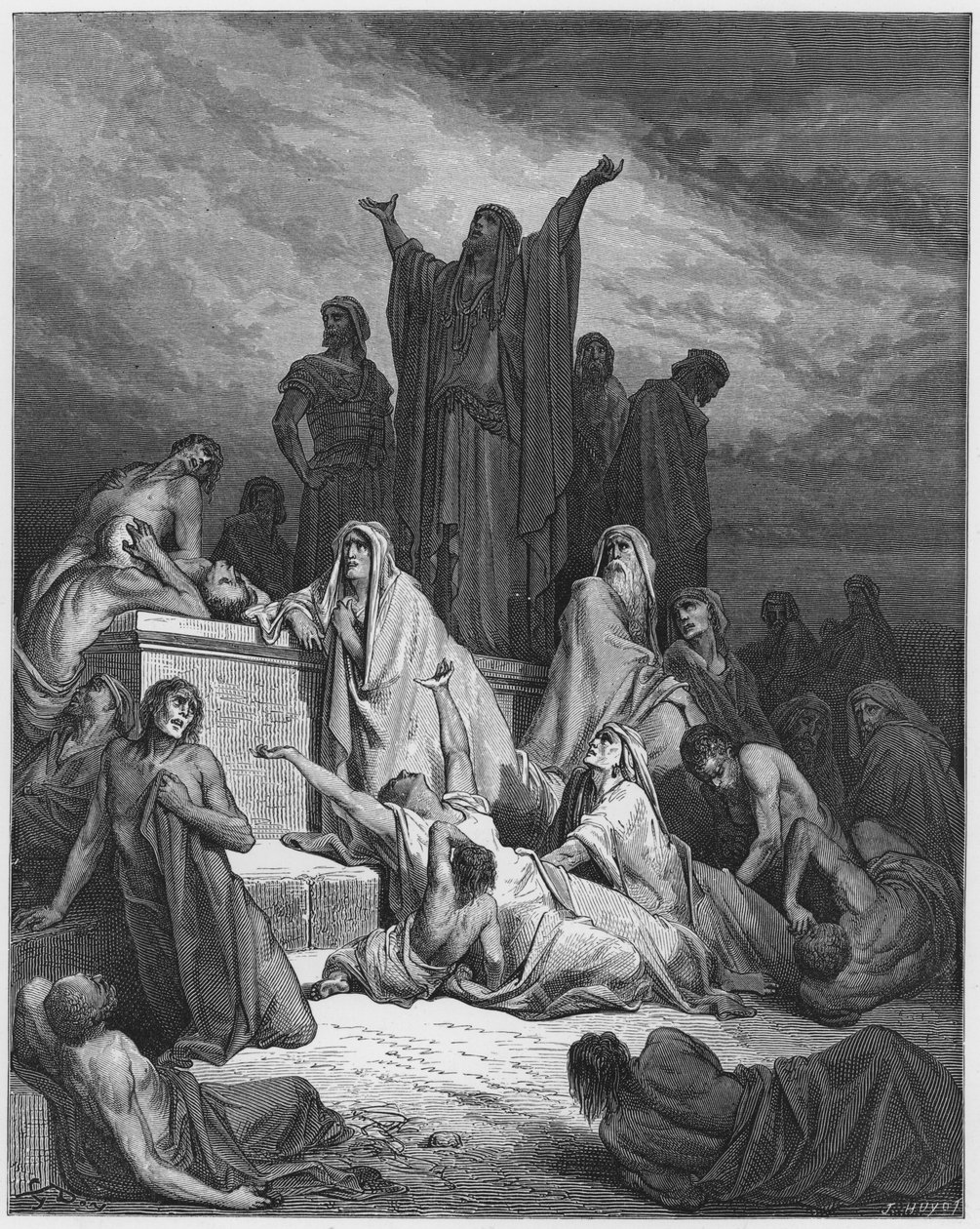

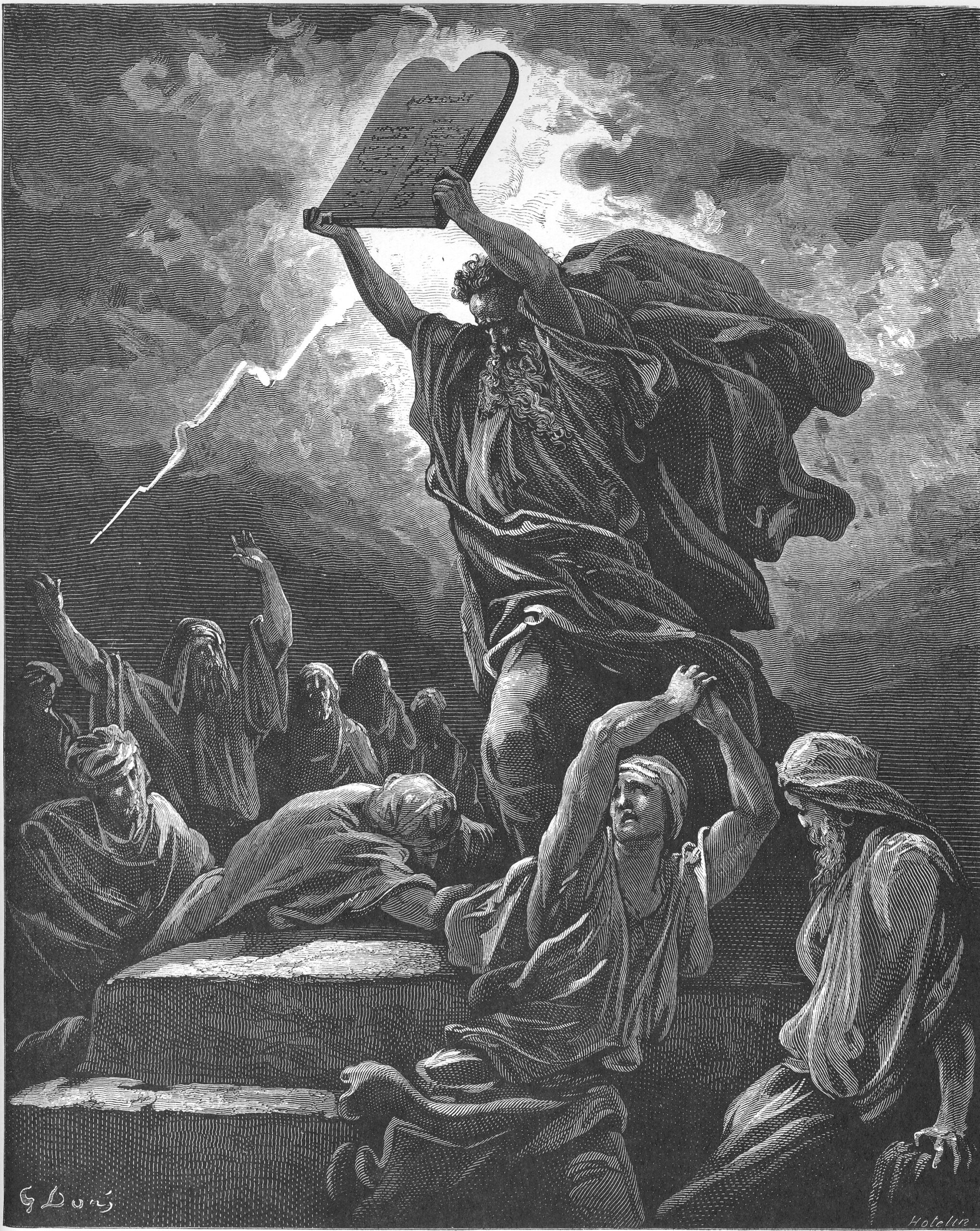

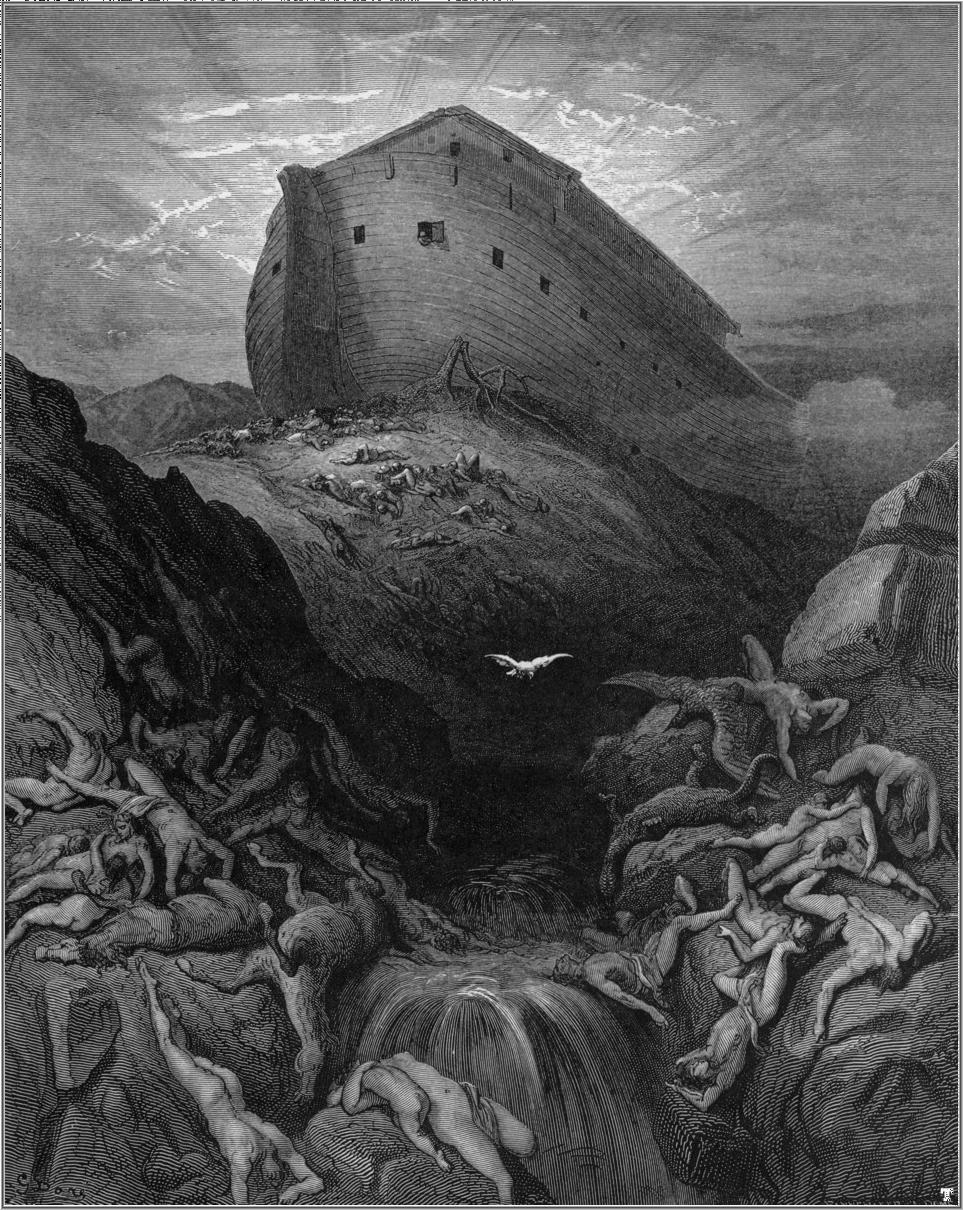

Doré took on the task of designing 241 engravings for a luxurious new French-language edition of the Vulgate Bible in the mid-eighteen-sixties. The project “offered him an almost endless series of intensely dramatic events,” writes biographer Joanna Richardson: “the looming tower of Babel, the plague of darkness in Egypt, the death of Samson, Isaiah’s vision of the destruction of Babylon.”

All provided practically ideal showcases for the elements of Doré’s intensely Romantic style: “the mountain scenes, the lurid skies, the complicated battles, the almost unremitting brutalism.” But along with the Old Testament “massacres and murders, decapitations and avenging angels” come Victorian angels, Victorian women, and Victorian children, “sentimental or wise beyond their years.”

Those choices may have been motivated by the simultaneous publication of La Grande Bible de Tours in both France and the United Kingdom. In any event, the edition proved successful enough on both sides of the Channel that a major exhibition of Doré’s work opened in London the very next year.

Though visibly rooted in their time and place — as well as in the artist’s personal sensibilities and the aesthetic currents in which he was caught up — Doré’s visions of the Bible still make an impact with their rich and immediately recognizable chiaroscuro portrayals of scenes that have long resonated through the whole of Western culture. You can see the whole series on Wikipedia, or as collected in The Doré Gallery of Bible Illustrations at Project Gutenberg — all, of course, for no charge.

Related content:

Gustave Doré’s Dramatic Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy

Gustave Doré’s Exquisite Engravings of Cervantes’ Don Quixote

Gustave Doré’s Macabre Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” (1884)

Salvador Dalí’s Illustrations for the Bible (1963)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.