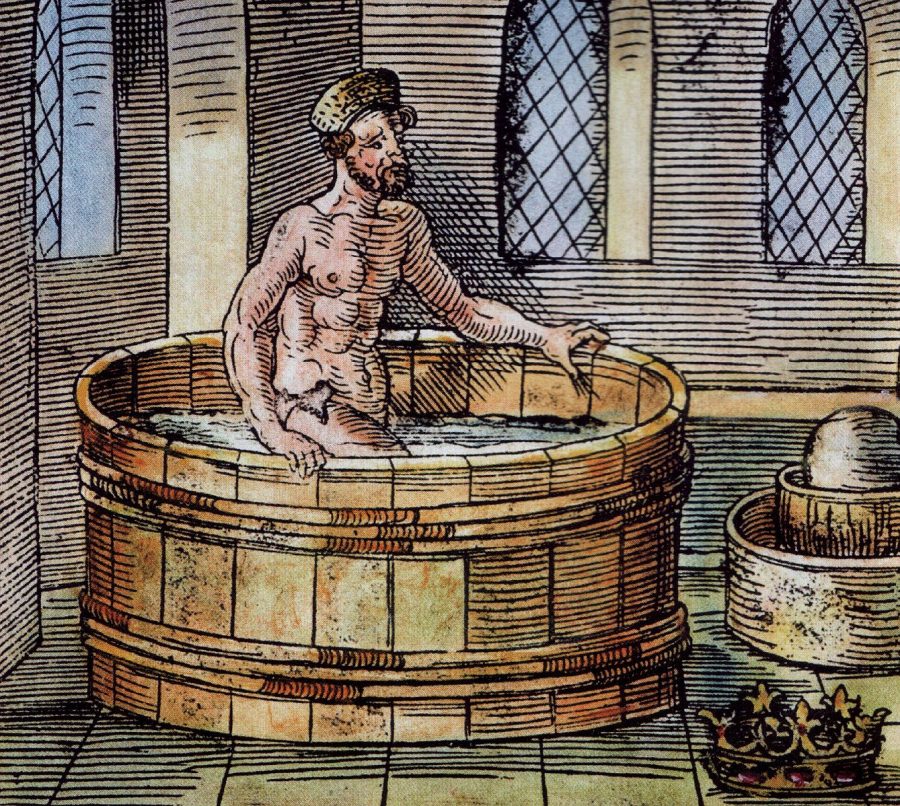

Image via Wikimedia Commons

“The great Tao fades away.”

So begins one translation of the Tao Te Ching’s 18th Chapter. The sentence captures the frustration that comes with a lost epiphany. Whether it’s a profound realization when you just wake up, or moment of clarity in the shower, by the time your mind’s gears start turning and you grope for pen and paper, the enlightenment has evaporated, replaced by muddle-headed, fumbling “what was that, again?”

“Intelligence comes forth. There is great deception.”

The sudden flashes of insight we have in states of meditative distraction—showering, pulling weeds in the garden, driving home from work—often elude our conscious mind precisely because they require its disengagement. When we’re too actively engaged in conscious thought—exercising our intelligence, so to speak—our creativity and inspiration suffer. “The great Tao fades away.”

The intuitive revelations we have while showering or performing other mindless tasks are what psychologists call “incubation.” As Mental Floss describes the phenomenon: “Since these routines don’t require much thought, you flip to autopilot. This frees up your unconscious to work on something else. Your mind goes wandering, leaving your brain to quietly play a no-holds-barred game of free association.”

Are we always doomed to lose the thread when we get self-conscious about what we’re doing? Not at all. In fact, some researchers, like Allen Braun and Siyuan Liu, have observed incubation at work in very creatively engaged individuals, like freestyle rappers. Theirs is a skill that must be honed and practiced exhaustively, but one that nonetheless relies on extemporaneous inspiration.

Renowned neuroscientist Alice Flaherty theorizes that the key biological ingredient in incubation is dopamine, the neurotransmitter released when we’re relaxed and comfortable. “People vary in terms of their level of creative drive,” writes Flaherty, “according to the activity of the dopamine pathways of the limbic system.” More relaxation, more dopamine. More dopamine, more creativity.

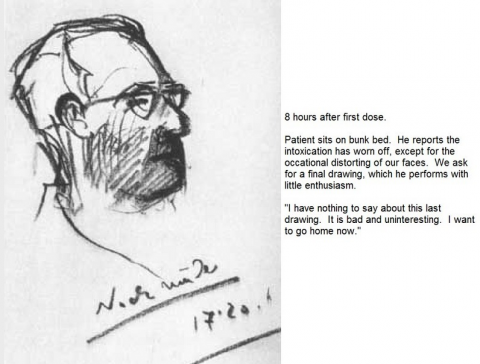

Other researchers, like Ut Na Sio and Thomas C. Ormerod at Lancaster University, have undertaken analysis of a more qualitative kind—of “anecdotal reports of the intellectual discovery processes of individuals hailed as geniuses.” Here we might think of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, whose poem “Kublai Khan”—“a vision in a dream”—he supposedly composed in the midst of a spontaneous revelation (or an opium haze)—before that annoying “person from Porlock” broke the spell.

Sio and Ormerod survey the literature of “incubation periods,” hoping to “allow us to make use of them effectively to promote creativity in areas such as individual problem solving, classroom learning, and work environments.” Their dense research suggests that we can exercise some degree of control over incubation, building unconscious work into our routines. But why is this necessary?

Psychologist John Kounios of Drexel University offers a straightforward explanation of the unconscious processes he refers to as “the default mode network.” Nick Stockton in Wired sums up Kounios’ theory:

Our brains typically catalog things by their context: Windows are parts of buildings, and the stars belong in the night sky. Ideas will always mingle to some degree, but when we’re focused on a specific task our thinking tends to be linear.

The task of showering—or bathing, in the case of Archimedes (above)—gives the mind a break, lets it mix things up and make the odd, random juxtapositions that are the essential basis of creativity. I’m tempted to think Wallace Stevens spent a good deal of time in the shower. Or maybe, like Stockton, he kept a “Poop Journal” (exactly what it sounds like).

Famous examples aside, what all of this research suggests is that peak creativity happens when we’re pleasantly absent-minded. Or, as psychologist Allen Braun writes, “We think what we see is a relaxation of ‘executive functions’ to allow more natural de-focused attention and uncensored processes to occur that might be the hallmark of creativity.”

None of this means that you’ll always be able to capture those brilliant ideas before they fade away. There’s no foolproof method involved in making use of creative distraction. But as Leo Widrich writes at Buffer, there are some tricks that may help. To increase your creative output and maximize the insights in incubation periods, he recommends that you:

- “Keep a notebook with you at all times, even in the shower.” (Widrich points us toward a waterproof notepad for that purpose.)

- “Plan disengagement and distraction.” Widrich calls this “the outer-inner technique.” John Cleese articulates another version of planned inspiration.

- “Overwhelm your brain: Make the task really hard.” This seems counterintuitive—the opposite of relaxation. But as Widrich explains, when you strain your brain with really difficult problems, others seem much easier by comparison.

It may seem like a lot of work getting your mind to relax, produce more dopamine, and get weird, circular, and inspired. But the work lies in making effective use of what’s already happening in your unconscious mind. Rather than groping blindly for that flash of brilliance you just had a moment ago, you can learn, writes Mental Floss, to “mind your mindless tasks.”

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2014.

Related Content:

Free Online Psychology Courses

How To Be Creative: PBS’ Off Book Series Explores the Secret Sauce of Great Ideas

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness