The word sophisticated may sound like praise today, but it originated as more of an accusation. Trace its etymology back far enough and you’ll encounter the sophists, itinerant lecturers in ancient Greece who taught subjects like philosophy, mathematics, music, and rhetoric — the last of which they mastered no matter their ostensible subject area. Their reputation has passed down to us our current understanding of the word sophistry as “subtly deceptive reasoning or argumentation.” A sophist may or may not have known what he was talking about, but he knew how to talk about it in the way his audience wanted to hear.

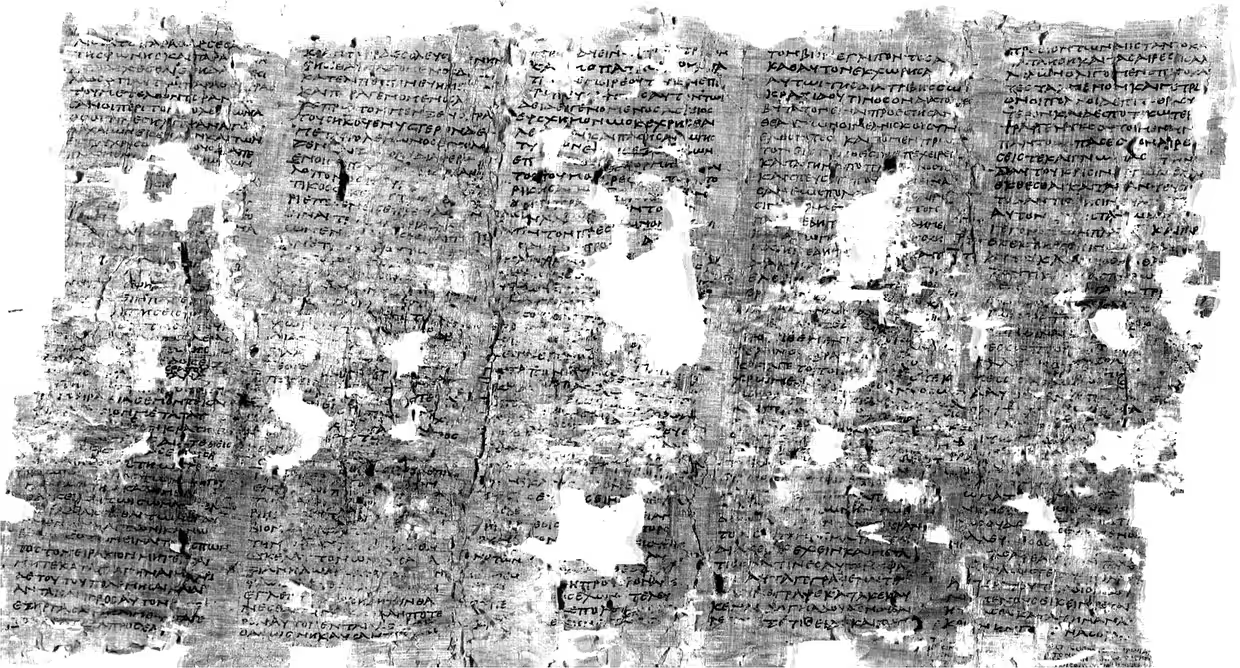

It is in the company of sophists that Plato places Socrates in the dialogue Gorgias, a section of which has been adapted into the short film above. An “experimental video essay from Epoché magazine,” as Aeon describes it, it “combines somewhat cryptic archival visuals, a haunting, dissonant score, and text from an exchange between Socrates and the titular Gorgias on the nature of oratory.” The latter describes oratory as his “art,” which serves “to produce the kind of conviction needed in courts of law and other large masses of people” on the subject of “right and wrong.” Socrates, in his questioning way, leads Gorgias to hear his objection that oratory produces conviction without knowledge, making it a mere pseudo-art or form of “flattery” akin to baking pastries or beautifully adorning one’s own body.

“For someone with no knowledge of the objects involved,” writes Epoché’s co-editor John C. Brady, “the arts and the pseudo-arts appear perhaps indistinguishable. But, insofar as the pseudo-arts focus on generating belief first and foremost (as opposed to rational justification) they have an advantage. In front of an audience of children, the chef will beat the doctor when it comes to demonstrating prowess in preparing ‘wholesome’ foods.” To that extent, Socrates’ basic observation holds up still today, more than 2,400 years after Gorgias. The situation may even have worsened in that time: “far from us moderns having a more ‘scientific’ (i.e. ‘artful’) approach to our action,” haven’t the pseudo-arts just “added to their repertoire the language of ‘knowledge’?”

Such enlightened twenty-first century men and women “clip on a Fitbit to track the minutiae of movements, download a ‘Pomodoro’ system app to record the when and the what of their work through the day,” use “calorie-counted food diaries, budget apps, online trackers that tell them how much time they are spending on Twitter vs. e‑mail.” Their eyes are on the prize of a balcony, a work-life balance; there’s often a carafe of wine airing in there somewhere too.” We believe that, in order to realize this dream, “we need to be scientific, rational, collect the data, work smarter not harder etc., etc. But haven’t we just here fallen into the orators’ trap?” All this “better living through data” starts to look like simple perpetuation of “the ease and pleasure of being ‘convinced’ by the many pseudo-arts, rather than grappling with the real objects that constitute the concreteness of our lives.” Wanting is fun; knowing exactly what we want and why we want it is philosophy.

via Aeon

Related content:

Literary Theorist Stanley Fish Offers a Free Course on Rhetoric, or the Power of Arguments

Jon Hamm Narrates a Modernized Version of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, Helping to Diagnose Our Social Media-Induced Narcissism

The Drinking Party (1965 Film) Adapts Plato’s Symposium to Modern Times

Why Socrates Hated Democracies: An Animated Case for Why Self-Government Requires Wisdom & Education

How to Speak: Watch the Lecture on Effective Communication That Became an MIT Tradition for Over 40 Years

How Pulp Fiction Uses the Socratic Method, the Philosophical Method from Ancient Greece

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.