|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Several weeks ago, Matt Mercer, state GOP communications director, reminded us of the often bruising dimensions of Jesse Helms’ career. Mercer reacted to a petition criticizing UNC-Chapel Hill administrators for how they handled pro-Palestinian protests; over 700 faculty and leaders signed the petition.

Mercer, in an X (formerly known as Twitter) post, announced that Helms was “right about Chapel Hill” when he criticized it as extreme left and out of touch with North Carolina.

Like many others, Mercer recalled a familiar story about Helms and the university (and town). Nearly all of the Chapel Hillians that I know remain convinced that Helms said “why build a zoo when we can just put up a fence around Chapel Hill.”

That statement is classic Helmsiana in his mocking of UNC as a center of elitists, along the lines of Alabama segregationist and southern Democrat George Wallace describing critics as “pointy headed intellectuals.”

The only problem is that Helms never said it. In researching my 2008 biography Righteous Warrior: Jesse Helms and the Rise of Modern Conservatism, I found no evidence that this statement was true. Some have attributed it to Henry F. “Chub” Seawell, a conservative lawyer and raconteur who denounced Chapel Hill’s “God-denying liars” and who occasionally filled in for Helms when he gave highly charged commentaries on WRAL-TV. But no evidence exists documenting Helms’ comment about the N.C. Zoo.

Mercer experienced considerable pushback from Twitter users on the left. Chrissy_NC, who identifies herself as a Democrat, sarcastically questioned whether Mercer spoke “for the entire [Republican] party when he praises a sexist, homophobic racist.”

Charlotte artist Luke Russell joined the spat, referring to the story that Helms once called UNC a “University of Negroes and Communists.”

There’s no evidence Helms ever said that either. The former director of the Jesse Helms Center in Wingate said the assertion was a “fabrication.” In December 2012, the Charlotte Observer printed a retraction after reporting that Helms had made that statement.

Russell admitted that the “Negroes and Communists” statement was apocryphal, but sarcastically asserted that Mercer had done a “great job” by “lowering the bar for our state once again.”

Sixteen years after his death, memories of Helms—TV journalist, guerilla fighter, apostle of modern conservatism, and five-term senator from North Carolina—have faded and sometimes been distorted. Even during his prime, many underestimated and largely misunderstood him. Senator George McGovern, who stood at the opposite end of the ideological spectrum, once called him “the dumbest man in the Senate.”

Nothing could be less true. His tactics were clever and have come to define the MAGA movement. Understanding Helms as an often-devious politician gives insight into the current breakdown of compromise politics.

Political Debate as Combat

In a buffoonish caricature, many on the left not only demonized but also marginalized Helms, portraying him as a small-town rube. In fact, he was shrewd and often personable.

At the same time, he approached political debate as combat. Frequently underestimated, Helms often bested his enemies and overwhelmed their defenses. He maintained an adroit correspondence with his liberal enemies. Although the Federal Communications Commission required that any broadcast editorial be open to a response, Helms typically had the last word.

As a senator, he mentored a new generation of conservatives, and today the Jesse Helms Center in Wingate maintains his legacy by housing his extensive manuscript materials. The center nurtures subsequent generations of conservatives, including those aligned with former President Donald Trump.

Helms also constructed an effective constituent-services team, using his Senate perch to help North Carolina liberals and conservatives.

At times, Helms worked across the aisle. As Foreign Relations chair, Helms struck up an alliance with the committee’s ranking senior senator from Delaware, Joe Biden. He also worked closely with President Bill Clinton’s secretary of state, Madeleine Albright.

Although for most of the 1980s and ‘90s Helms described gay AIDS victims as “perverts,” he played a critical role in curbing the disease’s spread in Africa. Helms hosted the Irish rock singer Bono, who was passionate about the issue, and successfully secured legislation providing AIDS medication to Africans who suffered from the disease.

But Helms, with his Carolina Piedmont drawl, also alienated members of both parties with his wily tactics. While conservatives profited from his politics of division, they never made him into an iconic symbol of their movement. Until 1995, when he became chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Helms used frivolous and usually unsuccessful amendments to force a vote, amplify issues, and spur fundraising.

He was a master rhetorician and a cagey strategist who was fundamentally underestimated by liberal opponents and progressive activists.

The Language of Opposition

Helms worked in Raleigh newspapers before and during World War II and pioneering radio and television journalism after it. He read and digested the ideas of conservative anticommunists and antistatists Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek.

By 1950, Helms had become a hardened ideologue. He relied on assertions of fellow southerners who claimed that Communist-sympathizing integrationists had created the New Deal state and were subverting southern segregationists’ attempts to preserve racial apartheid. As a sometime radio broadcaster and print journalist, he developed a message that was not openly racist, but suggested that the New Deal’s expansion of federal power was endangering whites’ property rights.

After working as a publicist and editor for the North Carolina banking industry, Helms tested out his message in print and broadcast journalism. That message connected issues of race, anticommunism, and antistatism in a wholesale critique of the cultural and political radicalism of the 1960s.

Beginning in November 1960, Helms began a 12-year stint as a television executive who delivered a five-minute “Viewpoint” editorial at the end of WRAL’s nightly news broadcast. These Viewpoint editorials—over 2,700 of them in total—mocked liberalism; criticized campus protest; blamed Black people for crime and drugs; attacked what he saw as excessive federal power in the New Frontier and the Great Society; and warned of impending social collapse that focused on fanning fears about the sexual revolution, crime, and Communist subversion.

Helms’ attacks centered on Martin Luther King Jr. and the African-American grassroots campaign against segregation, the revolt against racist oppression in cities, and federal intervention in the attempted desegregation of schools and public spaces. Helms often focused these attacks on King’s and others’ sexual proclivities. He also made homophobia (and, later, transphobia) a cornerstone of modern conservatism.

Helms sought to undermine modern liberalism and its supporters among intellectuals, the press, universities, government, and policy makers. He further questioned the left’s accomplishments and legacies—the civil rights revolution, the growth of the federal government at the expense of state and local power, rising taxes and a growing bureaucracy, and campus unrest and bohemian counterculture.

Helms was supremely effective in fashioning a language of opposition—creating a competing, conservative narrative—and, above all, in using the levers of the media.

“You can also bet that he will be remembered longer than Richard Burr, John Edwards, or others in future history books.”

Matt Mercer, NCGOP communications director

After 1950, Helms never again voted for a Democrat as he helped shape and define modern conservatism. His election to the U.S. Senate as a Republican from North Carolina in 1972—the first Republican to win that seat in North Carolina since 1898—coincided with Richard Nixon’s adoption of a Southern Strategy and with Republicans shifting to race-oriented attacks on their opponents.

After only a year in the Senate, Helms had become, according to one conservative reporter, a “shining star in the conservative galaxy.”

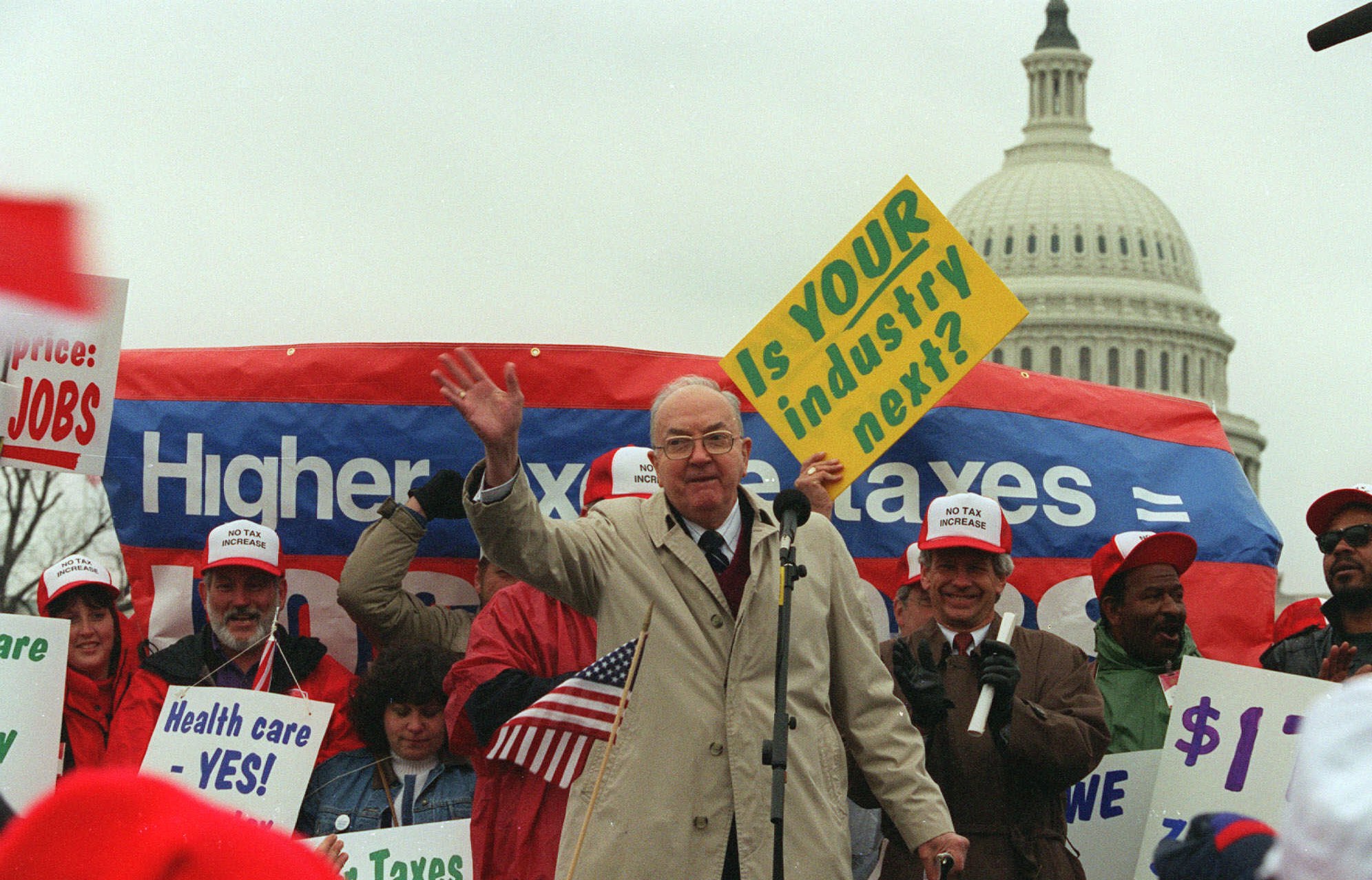

For five terms in the Senate, Helms was an obstructionist whose tactics today’s MAGA enthusiasts have adopted. During the 1970s, he pioneered the use of legislative amendments to push his agenda. Unlike other senators more skilled in thinking on their feet, Helms usually made his maneuvers after a great deal of preparation.

Helms accomplished little in passing legislation but focused on blocking bills and spending, bolstering his base, and fattening his fundraising coffers. He used the Senate as a platform for attack ads by the Congressional Club, his political organization that pioneered the use of negative political advertising. Attack ads became a standard part of late-twentieth century politics.

He also discovered how to tie the Senate in procedural knots and to employ opposition tactics to define new issues and mobilize conservative voters.

The Rise of Modern Conservatism

In an email exchange, Mercer noted that he admired Helms despite not having been old enough to vote for him; Helms last ran in 1996. Like Helms, Mercer began his career in media and then became involved in politics.

He noted that conservative Democrats—they were called “Jessecrats”—voted for Helms and appreciated his ability to represent them. “You can also bet,” Mercer wrote, referencing two other North Carolina senators, “that he will be remembered longer than Richard Burr, John Edwards, or others in future history books.”

While Helms indeed was historically significant, most national observers have forgotten his ideology and politics, even though MAGA Republicans have adopted the same tactics. The filibuster, which Helms deployed to the irritation of politicians of both parties, has paralyzed the Senate; the moderate center that used to dominate Congress and smoothed the way for effective governance has largely dissipated.

Helms’ partisans regarded any notion of fostering Republican Party unity as “nonsense,” remembered a reporter. Helms despised the very notion of compromise. Although traditionally many lawmakers saw politics as the art of compromise, Helms viewed governing as “a challenge to provide principled leadership.” A political party that could not follow “a forthright course of action to inspire the nation to rise to greatness is a political party that will wither and blow away.” Why, he asked, should conservatives “shrink from truth in the pursuit of expediency?”

Today the political system, in North Carolina and elsewhere, is acutely polarized, with the disappearance of pragmatists in both national political parties. Helms’ confrontational brand of politics contributed to the rise of modern conservatism on a national stage. Long before X existed, Helms steered us toward the political world that we inhabit today.

Historian William A. Link taught for 23 years at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and for 19 years at the University of Florida. Both of his parents were native North Carolinians. He is the author of biographies about Jesse Helms, William Friday, and Frank Porter Graham. He lives in Snow Camp in Alamance County.