On April 15, 2018, fighting broke out at a rural South Carolina prison, becoming the deadliest explosion of U.S. prison violence in 25 years.

Officials have said little publicly about what happened.

This is the story of that night.

—

A group of men plays cards at a steel table bolted to the concrete floor. They keep one eye on the deck, one eye over their shoulders.

Springtime air thickens over Lee Correctional Institution and the cotton fields that sprawl in the distance. Damp from the coming downpour clings to narrow windows that peer into a dorm at the maximum-security prison where violence has flared more often lately.

The card players sit in the center of their cellblock, an area known as The Rock. On a nearby TV, other men watch the evening's NBA playoffs. The Utah Jazz are battling the Oklahoma City Thunder. It’s Game 1, a tight one.

Before the violence exploded, men inside Lee Correctional Institution's F-3 unit played cards and watched NBA playoffs on TV. Andrew Whitaker/Staff

Few notice inmates slip into Michael Milledge’s first-floor cell, tucked near one corner of the cavernous building.

At 44, Milledge is an elder by prison standards. Over the last eight years, he has lived on five of South Carolina’s six maximum-security yards and built a reputation for acquiring drugs, cellphones, weapons and money.

Things that other inmates want.

Lately he’d been lying low, posting inspirational memes on Facebook and devoting days to the law library working on his conviction appeal. A judge had granted him a new trial on his drug and gun-related charges.

Milledge felt hope — until a month earlier when the state Supreme Court denied his appeal. A pat-down during a traffic stop did not violate his rights.

Days after, the father of four shared a post: “DON’T EVER LET SUCCESS GET TO YOUR HEAD OR FAILURE GET TO YOUR HEART.”

Yet, here he is at Lee about to die.

Some inmates later hear the men have gone into his cell to steal his TV and personal items. Others hear they want money owed. Or drugs. Or a package of contraband. Or a single cellphone, worth $700 to $1,000 to men locked away from the world.

Any scenario is possible. And common in South Carolina's prisons.

When state corrections officials have failed to keep inmates safe, where rules ban desirables like phones and drugs, gangs fill the vacuum. And this building is newly filled with rival gang members.

Milledge arrived five months ago in a mass transfer aimed at easing dangers at McCormick and Broad River correctional institutions, both sites of recent major inmate disturbances. Milledge came from Broad River.

Among the larger group from McCormick is Damonte Rivera, a man everyone calls Hammer, who once described himself as a small truck with a big engine. He landed in prison a few years ago, barely 20 years old with a life sentence for murder.

Rivera is one who slips into Milledge’s cell, although the door should have been locked.

Michael Milledge, 44. S.C. Department of Corrections/Provided

When Milledge defends himself, and his stuff, it turns violent. He tries to block the blows, but a shank slices his head. It sinks into his abdomen over and over.

The inmates soon emerge from his room. One man runs, but Rivera stops on The Rock. When men confront him, he taunts them.

“What motherf---er, you want some of this?”

Reaction is certain. A Blood gang member runs up and stabs Rivera in the neck.

A sound like shoes squeaking on a basketball court fills The Rock as men respond. Some head for their comrades. Others flee to their cells. A few hurry to Milledge’s room. They find the man choking on his own blood.

He’s alive. Barely.

Inmates look for a correctional officer, given one is supposed to be on the wing.

But they don’t see any.

The historic violence at Lee Correctional Institution began inside its F-3 housing dorm. Andrew Whitaker/Staff

To understand these moments when Rivera and Milledge cross paths and spark an historic night of violence, you must understand a crisis that prompted the mass transfer of men into Lee.

You also must understand the gangs among them that control violence, money and contraband — which is to say, power.

And a door-locking system those men could easily defeat.

And a security staff with little control.

And so many hopeless, angry men.

Even before the mass transfer, Lee was a violent place. Over the years leading to these moments, inmates had taken officers hostage, threatened them, brutalized one another, and killed each other. They had dragged each other into cells for beatings and dragged each other out for stabbings — typically by shanks and axes hand-crafted from any scrap of metal, paint or plaster they could sharpen to a razor's edge.

But more recently, Lee also faced a dire shortage of staff.

In June 2017, the state Department of Corrections hired Tom Roth, a national prison expert, to study security staffing needs. He found that Lee had averaged 111 front-line officers in the second half of 2017 — 80 fewer officers than it had in January 2012, when the recent drop in staff at Lee began. Roth thought the prison needed 258.

An inmate inside Lee's F-3 dorm makes a phone call. Andrew Whitaker/Staff

The problem wasn’t unique to Lee.

By then, Michael McCall, the agency’s deputy director of operations, faced a crisis. Six of his prisons were functioning with fewer than 50 percent of the security staff they needed. The agency struggled to fill positions with high stress and low state-funded pay, as an expanding statewide economy created more desirable job opportunities.

Lee was bad.

But two hours away, McCormick Correctional was worse.

By fall 2017, the warden and senior staff had left. Senior security officers were on extended medical leave. Front-line staff dwindled. One day, two officers showed up for roll call to work a prison with almost 1,000 inmates.

So the inmates did what they wanted. At one point, 200 were ignoring their dorm assignments, living in cells that they chose. In early October, in the final straw for McCall, inmates took over McCormick’s restrictive housing unit — home to the most dangerous, troublesome offenders — and terrified officers before getting onto the prison’s roof. Gangs ruled the yard.

McCall feared losing all control of McCormick.

He feared people dying.

At McCormick, the officer vacancy rate pushed 60 percent. Lee's was lower. And the prison had room. Its Addiction Treatment Unit housed 80 inmates in a space that could fit three times that.

He sent Lee’s warden, Aaron Joyner, a list of inmates coming to him.

In an Oct. 23 email to McCall and other managers, Joyner objected. The inmates were the “worst inmates throughout the prison,” gang members involved in disturbances with ties to the area. He preferred to separate leaders and move a few men at a time.

“I am asking that you look at removing a lot of these ring leaders off this list and not put a lot of these inmates in the same prison so they can try to regroup,” Joyner wrote.

Inmates wait to be transported on a bus outside of Lee Correctional Institution. Andrew J. Whitaker/ Staff

McCall struck inmates from the list and mixed in some new names.

Then he made a fateful decision.

He shipped the 80 inmates receiving addiction treatment out of Lee — and began to move 256 men from McCormick into the space.

In waves, they boarded white prison buses to drive two hours to Bishopville, a rural outpost northeast of Columbia. Another mass transfer of men from Broad River in Columbia followed.

By Christmas, 335 new inmates had arrived at Lee. Most had histories of trouble in prison or were involved in gangs, though prison leaders lacked the staff to gather enough intelligence to know the depths of it. Many were killers. Others were doing time for drugs and burglaries.

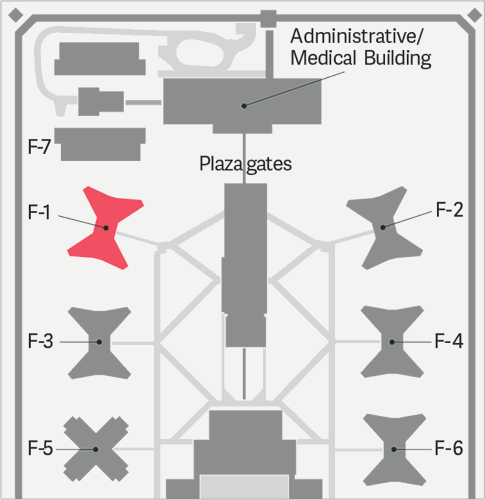

They moved into Lee’s dangerous West Yard, where four hulking dorms loom in a row. Most entered a middle building called F-3.

Their arrival changed the prison in what experts later called “dramatic and persistent ways.”

You see, South Carolina’s maximum-security prisons are like revolving doors. If a man has a beef with someone, he’ll likely see him again. Crammed together at Lee, many saw familiar faces.

An inmate in Lee's restrictive housing unit peers at people entering the wing, which houses the prison's most problematic inmates. File/Andrew Whitaker/Staff

After being stabbed inside his cell in F-3, Michael Milledge struggles for life. Out in the common area, inmates approach The Rock wearing masks to hide their faces from security cameras that always watch them.

It feels like a terrible kind of Halloween.

Tightening tensions, intensified by gang rivalries, are about to snap.

The Bloods comprise the largest gang here and at prisons across the state. Normally the Crips and Gangster Disciples, called Gs, work together to balance power.

But not now.

Rivera is a G, and the outnumbered Gs face the Bloods.

Inmates flood The Rock. Others flee to their cells and try to jam shut the metal doors that officers have left unlocked. Blood splatters onto the scuffed beige floor. Men scream as others force their way into cells, stabbing them with homemade weapons, some exacting revenge, some just joining the frenzy.

Eddie Gaskins and Daman Strickland are among the newest men at Lee. Gaskins, a 32-year-old who hails from Berkeley County, just inland from Charleston, got here barely two weeks ago. Strickland arrived just 12 days ago for drug and theft charges.

With a third man, they sprint into Gaskins’ first-floor cell and try to hold the door shut. It works, until an attacker breaks the window with a hammer. Inmates force their way in and attack all three, repeatedly stabbing them.

Eddie Gaskins, 32. S.C. Department of Corrections/Provided

Strickland’s lung collapses. A blow breaks his teeth. Stab wounds cover his head, neck, arm and side.

Gaskins tries to protect himself. The father of four, serving time for domestic violence, will be eligible for parole in November 2019.

Instead, he lies bleeding to death from 46 jagged cuts.

As violence explodes on the building’s B-Wing, Officer Holmes, who has manned F-3 by herself all day, prepares to leave.

Her replacement, Officer Mingo, arrives for the overnight shift. The building is supposed to have at least two officers working at a time, one on each wing.

But it doesn’t.

Because of the staff shortage, Mingo also will work alone with the 256 inmates who live here, pepper spray her main protection.

Around 7 p.m., she signs on and stands at the B-Wing officer station with Holmes, who was supposed to be off today but came in to cover a shift.

About two-thirds of officers are women. To some inmates, their presence creates drama. Men with endless days and decades of time already jockey hard for money and rank. With female officers, they also vie for attention and sexual interest.

Mingo heads to a sally port area that connects the two wings. Doors to each are supposed to be locked.

But they aren’t.

As Mingo starts her shift, she hears a commotion and sees inmates pouring out of the B-Wing into the sally port. They brandish shanks and homemade axes. She screams and sprints through a doorway to the A-Wing. Behind her, the wing door remains unlocked.

An inmate she has spoken to before lets her into his cell. He barricades the door.

Officer Holmes hurries into the sally port. Inmates pour in around her.

Damonte Rivera, 24. S.C. Department of Corrections/Provided

They have Damonte Rivera.

Not 5 feet away, they chop and stab his body. Blood sprays everywhere. She yells for them to stop.

Several look at her.

“Just back up,” a man warns her. “Just back up.”

She’s trapped. The building’s steel front door, just feet away, is locked, and she doesn’t have the keys. As she steps toward a wing in search of safety, an inmate cautions her not to come any closer.

“If you come on the wing, you’re going to get killed,” he says, urging her to find safety.

She struggles not to lose her cool and darts into a small room.

James Lee Williams is leaving the shower nearby when he hears yelling. He steps into the sally port to find out what’s going on and sees the inmates stabbing Rivera. The attackers flee. He and others pull Rivera's body to the A-Wing with them, though he seems lifeless.

Then they try to barricade the unlocked door to their wing, desperate to keep the armed killers from getting in. On the other side, a large group of Bloods return. They press against the unlocked door, pounding and shouting threats.

It heaves with the force, but the men hold it closed. For now.

Lee Correctional Institution's notorious West Yard includes, from left to right, its F-5, F-3 and F-1 units. Andrew Whitaker/Staff

Normally, leaders from the major rival gangs — Bloods, Crips and Gs — coexist on a prison yard. Violence is meted out when necessary, but it can be bad for business. Peace allows drugs and cellphones — and therefore money — to flow.

The surge of new men into Lee upset the order. New guys claimed gang affiliations and rank. They brought old vendettas with them.

They also drank booze, smoked weed and got high on ecstasy. They made deals on illicit cellphones. The prison had a contraband team, but it was down to three active members, and they almost always got assigned to other duties to fill gaps caused by the staffing shortage.

Prison leaders grew frustrated. Staff grew fearful.

Inmates grew brazen.

As tensions swelled, inmates broke their windows to fashion the metal stripping into weapons. Officers heard them sharpening blades. Men were preparing for battle.

In November 2017, one inmate killed another inmate. Another was slain in February. In March, men in the restrictive housing unit took an officer hostage.

Red flags, each of them.

Prison leaders could have locked down the yard and called in the agency's search team. Lee was too understaffed to perform many random searches of inmates or cells, although in February and March, its stretched-thin officers still found 67 homemade knives and 62 illicit cellphones.

In fact, just five days before the killings began, the agency's search team had come to Lee — and swept its less-problematic East Yard.

Prisoners on the West Yard continued to sharpen their weapons. Violence and thirst for retribution spread.

In a snapshot of normal life at Lee in 2017, an average of seven inmates were severely wounded in assaults every three months by other prisoners.

But over the first three months of 2018, that number soared to 19.

Yet, prison officials conducted no serious incident reviews to see how to prevent more of it.

Now it’s April, and three men lie dying.

Inside the control room of Lee's F-5 dorm, an officer watched as inmates in the surrounding pods battled. She was trapped inside for more than eight hours. Andrew Whitaker/Staff

Around 7 p.m., as Milledge, Rivera and Gaskins bleed in F-3 and their fellow inmates struggle to hold the wing door closed, shift change also takes place in a dorm next door, F-5. It is the last of four drab gray dorms on the West Yard.

Officer Anderson assumes the helm of the control room in the unit, a concrete bunker with a dark green roof that roll call count shows is home to 252 inmates that night.

She, too, will work alone.

Anderson is known among the inmates as an officer who cares about her job and goes by the book. As duty requires, she picks up a pen to fill in the unit’s logbook. In her first entry, at 7:15 p.m., she notes that first responders — officers assigned to help with problem areas around the prison — have been called to F-3 next door.

The other dorms at Lee are laid out like F-3: two big wings connected by a sally port.

F-5 is laid out differently. Anderson sits alone in a raised control booth at the center of four pods that sprout around her like a four-leaf clover. Each houses 64 men in two tiers of cells, giving them a much smaller feel than the large wings in the other buildings.

Through banks of thick windows encased in metal bars, Anderson can see everything that happens in the pods. With so much visibility and a secure place for the officer looking out, it should have been the safest design in the entire prison system.

At 7:30 p.m., she updates her log: “Front doors are open inmates walking back & forth.”

Fifteen minutes later, with fresh darkness blanketing the prison, she adds: “There are a lot of inmates walking from pod to pod.”

They are standing around in groups.

Some cover their heads.

She can’t do much about it. The men go where they please. Years ago, inmates in F-5 had learned to manipulate its locking system, a design used in five prison housing units across the state.

The doors in F-3, and all the other housing units at Lee, are locked manually with a key. F-5 is different.

Their doors don’t swing open like in most cells. They slide shut using air pressure, which the men can overpower. A locking bar also falls into a slot to fix the door open or shut. But inmates have figured out they can shove something into the slots to prevent the locking bars from falling into place.

Then they can slide their cell doors open at will. Which they do.

With one officer alone in the control room, who is going to make them stay anywhere?

Lee's F-5 dorm is the last housing unit on its West Yard. Inside, four pods surround a central command room. Andrew Whitaker/Staff

The locking system had long been a concern.

Michael McCall served as warden of Lee in 2012 before ultimately becoming the prison agency’s deputy director of operations. By then, it was clear that inmates could defeat F-5’s locking system.

In December 2016, after selecting manual locks to install on the cells, prison managers ordered enough to try out in one pod.

Then they waited.

The locks arrived in June 2017, the month prison leaders asked Tom Roth to examine security staffing. But the agency was working on cell lock projects at other prisons, too, and had only two employees doing the work. Lee would wait.

McCall warned subordinate managers about the importance of moving forward:

“This is an emergency,” he typed.

On Nov. 1, 2017, crews finally installed the new locks. But they only covered one of F-5's four pods, and the fire marshal hadn't approved their use yet. Locks for the other three pods wouldn’t be shipped until March or April.

While prison leaders waited, violence marched across the West Yard.

On Jan. 23, Crips attacked one of their own in F-5.

On Feb. 15, an inmate assaulted a fellow inmate in F-5 when the prison was supposed to be on lockdown after an earlier attack.

On March 15, two masked men attacked a prisoner with a metal pipe and ax. That night, one inmate in F-5 stabbed another in the stomach.

On March 17, McCall emailed a half-dozen agency managers asking if they’d done everything to keep inmates from defeating the current locking system while they waited for new locks:

“I must be sure without a doubt we are doing everything we can to get this resolved for the safety for our staff and the safety for the public.”

Cell doors inside of the F-5 dorm at Lee Correctional Institution. Andrew J. Whitaker/ Staff

Back in F-3, James Lee Williams and other inmates still cling to the door between the building’s two wings in a desperate bid to contain the bloodshed. If the killers get in, they will reach the 128 men living in the A-Wing.

The inmates cannot rely on prison security staff to save them. The officers are too few and no match for inmates with shanks, axes and pipes.

The men wonder if they will die tonight.

They can’t hold the door shut forever. Finally, inmates on the other side force it open enough to shoot pepper spray at them.

The dam breaks.

A swarm of men from B-Wing, many wearing masks, flood into the A-Wing where inmates have fled for safety and where Officer Mingo still hides in a cell. Williams turns to run, but another inmate bashes him in the head and spine, then stabs him in the head and thigh.

Another man joins a group dashing up a staircase leading to the second floor of cells. Attackers swarm in pursuit as they race into a cell and barricade the door shut. Inmates try to smash its narrow window.

When the glass holds, one yells: “God is on your side today!”

The attackers move on.

Men hiding in the cell flee. Seeing no better option, one stays put.

Several marauders return. They stab the inmate who stayed behind 14 times with homemade knives and icepick-like weapons. One uses a sharpened square of metal shaped like a hatchet to fracture his skull.

They tell him he’s going to die, and he believes them.

In another cell, inmate Jadarius Roberts also tries to hold a door closed. But the men overpower him and burst inside, stabbing him more than 20 times.

Just before Roberts passes out, he hears: “It’s time for you to die.”

The men move on to others.

Metal banging on metal, desperate men screaming for their lives, and the angry taunts of threats careen off the unforgiving walls of F-3. The inmates have gotten hold of an officer's prison radio, which some are using to call for aid.

Video from inside Lee Correctional culled from inmate social media posts.

At 7:43 p.m., state prison leaders activate a regional tactical team trained to handle riots that will show up with rubber bullets and riot gear.

At 8:25 p.m., they activate all of the agency’s tactical teams.

Before Lee's staff can do much else, they must wait for the teams to arrive. It will take hours. Team members drive from their homes or prisons where they are working all around the vast, rural part of the state.

Meanwhile, inmates use their cellphones to post videos and pictures on social media of bloody bodies and men stalking around with shanks. Families of the wounded and dying men see them. The images spread across social media.

An inmate who was injured in the violence describes what happened in a letter to The Post and Courier. Andrew J. Whitaker/ Staff

Two of the prison's first responders gather outside of a side door into F-3 away from the fighting. One cracks it open and peers inside. She sees an inmate nearby and asks where Officer Mingo is.

She is safe in a cell, he says.

When the officers give the OK, prisoners tell Mingo to come out. She races to the door and escapes unharmed. The officers get Holmes to safety as well. Inmates aren’t after the staff.

But men see the first responders are there and begin dragging wounded men in that direction hoping to get them out, too.

Video from inside Lee Correctional culled from inmate social media posts.

Desperate to save his life, friends rush Damonte Rivera’s limp body to the door. One is Anthony Fraser, a guy from his hometown who went to prison with him for the same crime. He too is seriously wounded.

When the door opens, Fraser and the other inmates hurry outside with Rivera. They carry him around to the front of the dorm, then across the West Yard and toward a gate that leads to the administration building. Inside sits the medical area with a small emergency room.

If they can make it there, perhaps Rivera will survive.

They pass a dorm called F-1 where inmates whose cell windows look out over the yard see the men carrying Rivera's motionless body. They watch other bloodied men going to medical.

Anxious to learn what's going on, they huddle at the windows or find their fellow gang members. Some grab their cellphones.

Did the Bloods kill Rivera?

Who else in F-3 is dead or injured?

And how are the gang leaders going to respond?

The officers at the side door have just gotten a few injured men out of F-3 when they get a call over their prison radios. An inmate is loose on the yard — a high-ranking gang member who arrived a few days ago. Some hear he has a hit out on Raymond Scott, a top Blood who lives in F-5, the last dorm on the West Yard.

Before the violence can spread to other dorms, the officers must go help find the prisoner. They lock the side door and head away, leaving terrified inmates trapped inside the building.

Men still lie bleeding, dying. Inmates still stalk the wings with shanks. Who is going to help them?

In desperation, they try 911.

Medical crews inside Lee's emergency room worked for hours to try and save dozens of men who suffered severe injuries, including some who died. Andrew J. Whitaker/ Staff

Around 7:50 p.m., an inmate calls 911 hoping that someone will send help before more men die. After 25 seconds of ringing, a dispatcher answers.

“Central dispatch.”

“Yes, I need first responders ASAP, immediately," the man says. He asks that an ambulance be sent to the prison. "It’s been several stabbings and casualties laying out on the floor, man.”

“Who am I speaking with?”

“I’ll never tell you that. But I’m telling you it’s going on right now, man.”

“Are you an inmate there?”

“Yes, I am an inmate, but it’s gang members going against each other, man. It’s Bloods against the Gs.”

“What unit is this going on in?”

“It’s going on in F-3, F-3 — both sides, man,” he says. “I'm trying to get you guys down here to help us, man …”

The dispatcher cuts him off: “Sir, listen to me, what is the name of the unit?”

“Sumter unit, F-3, F-3, man.”

“All right, we got units in route.”

Roderquiz Cook is one of two inmates working in the prison’s infirmary, tending to elderly and sick prisoners. He heads for the plaza gate to help Fraser and the two other inmates hauling Rivera.

Cook recognizes the men immediately.

Just a week and a half ago, Fraser showed up at a class that Cook teaches inmates every Thursday called “Things Men Should Know.” It’s his mission, a way to share wisdom with the prison’s younger guys.

Fraser had come to him for help. He’d mentioned Rivera, wondering if his friend would benefit from the class. Rivera was young, often bursting with energy. It needed to be channeled.

Cook had encouraged Fraser to bring him. The next class was supposed to have been three days ago. But it got canceled.

Shocked at what he sees, Cook rushes to help Fraser put Rivera on a stretcher and lug him through the plaza gate, then into the prison’s emergency room.

There isn’t much time.

Rivera has a hole in his neck the size of a 50-cent piece. Fraser bleeds too as he clutches his friend’s hand, urging him to keep breathing, demanding officers and staff do everything they can to save Rivera. A nurse starts CPR.

Lee County paramedics arrive and take over.

They rush Rivera toward an ambulance, but his heart stops beating.

Cook watches the young man die. Failure overwhelms him. If only Rivera had come to his class. If only he could have gotten to him.

If only he could have shown him a better path.

Around 8 p.m., another man dials 911 from a cell.

“I’m an inmate at Lee County Correctional Institution and there’s inmates in here trying to kill me.”

The call drops. He dials back.

A second dispatcher answers. The man explains again: He’s an inmate at Lee.

“Inmates in here trying to kill me.”

“All right. I’ll try to get somebody to you. What’s your name?”

He doesn’t want to give his name. He’ll get in trouble for having a cellphone.

“We need help quick,” he pleads. “They coming! They trying to bust down the doors and all.”

“Please, man. Help me, man. They out there right now trying to beat down the door. I need help.”

The dispatcher hangs up and calls the prison. The woman who answers says they are waiting for a special team to come. She sounds distracted, discombobulated.

“We’re looking at the camera now,” she says. Then she passes him off to a commander.

“Hold on one minute,” the dispatcher says. “Are they actually trying to get to that particular person that’s calling in here?”

“Yes," the commander answers, "he’s barricaded in his door, and they trying to beat the door in. But that door is not moving.”

The inmates are out, she adds. And the officers have left.

She doesn’t mention that paramedics have asked for the coroner.

At 8:15 p.m. in the medical ward, paramedics move Fraser, distraught over Rivera and hit in the head with a makeshift ax, into an ambulance. Two corrections officers go with him.

Two officers must escort every inmate who leaves, stretching an already thin staff. An unarmed officer rides in the ambulance; an armed one follows to ensure no escapes. Yet, with only 44 staff on the entire campus of 1,583 inmates, they can spare no one.

The officers who just escaped F-3 leave with the next wounded men, no time to process what they've just witnessed.

At 8:45 p.m., paramedics rush away with Michael Milledge, the first man attacked tonight. Guarding him is Officer Holmes, who just watched inmates brutalize Rivera feet away from her.

Fifteen minutes later, an ambulance leaves with another inmate. Officer Mingo goes with him.

More ambulances arrive. A medevac helicopter is called but it cannot come due to the gathering storm.

As ambulances leave, word of the violence spreads across the 50-acre prison compound. Tensions steep with suspicions of what's happened — and what should be done about it.

Still holed up in the F-5 dorm's control room, more than an hour after her first entry, Officer Anderson updates her unit’s logbook: “Doors are not secured, inmates cont to stand around on the outside.”

Inside the control room of the F-5 dorm, an officer watched violence explode among inmates. Andrew Whitaker/Staff

Men mill around F-5, rival gangs are on edge. Some text and call friends in the prison's other buildings. They watch inmates' cellphone videos of a man splayed on the floor and a bloody body being carried through a neighboring dorm.

Some don handmade protective clothing that bind prison uniforms, bedding and scraps of metal together to lessen blows from weapons.

Bloods gather under TVs hanging from the ceiling in one of the pods. Crips and Gs stand across from them.

How should they respond to the killings next door?

Raymond Scott, the high-ranking Blood, tells a close friend to get dressed and be alert.

Scott goes by “Twin” because he had a twin brother, gone now, killed in a shootout six years earlier. The twins were 22 then. They hailed from North Charleston, a growing city pockmarked with high-crime areas.

Just hours ago, Scott's mother had driven up to visit him. Afterward, on his way back to the yard, Scott told officers: “This might be my last time seeing y’all."

People have heard there is a hit out on him.

In the view of some, Scott runs the yard and keeps the peace among prisoners here. He helps officers out, and they rely on him to stop conflicts. He tells them when something is about to go down, or when they need to leave so inmates can conduct business.

Not everyone sees him that way though, especially not all the Crips and Gs. Some inmates think he and other Bloods work with the administration to get leeway for themselves at the expense of others. They see officers affiliated with the gang, or at least willing to work with it.

And now they hear Bloods are killing their friends in F-3.

Will they come after them next?

Raymond Scott, 28. S.C. Department of Corrections/Provided

In many ways, this is like war. Calculated decisions are made from the top, but the battlefield can be chaotic. Some information trickling down to those on the ground is wrong or incomplete. Not everyone in F-5 knows the violence started when men robbed Milledge. Some think the Bloods killed rival gang members next door for no reason.

Calls and texts update them about the situation in F-3 and bring directives from higher-ranking members who call the shots.

Orders come for united action.

Crips and Gs start threatening the Bloods. Dozens of armed inmates back a big group of them into a corner, yelling threats.

Men start swinging shanks. An inmate coming out of his cell gets smashed in the face with a homemade hatchet. Around the unit, men fall bleeding.

At 9:05 p.m., from the building's control room, Anderson calls for the prison’s first responders. She, at least, is protected by two steel doors.

Help doesn’t come. There aren’t enough officers at the prison to risk going in.

The Bloods try to defend themselves, but they are outnumbered.

A chant breaks out: “Kill Twin!”

The united Crips and Gs order Scott and the other Bloods to leave the building. When they refuse, the armed men attack them.

As they fled the F-5 dorm, inmates faced a decision: get attacked by rival gang members with shanks and axes, or climb the razor wire fence. Andrew Whitaker/Staff

Outside, 12-foot tall razor-wire fences ring the building. They also enclose a front sidewalk, which juts out into the West Yard for everyone to see.

A gate, the only way out, sits at the end.

Finally, the Bloods rush for the building's front doors. The attackers pursue. Weapons land blow after blow.

Around 9:25 p.m., more than two hours after violence exploded next door in F-3, a mass of men in F-5 now race out the open front doors and into drenching rain. About two dozen of them sprint down the dark sidewalk. If they can reach the gate ahead, they might get out into the yard to find help.

The gate isn't always locked.

Instead, they see an officer standing outside the gate check its lock. When the armed, screaming inmates pour out of F-5, the officer takes off running toward the administration building for safety.

The prisoners reach the locked gate. They see no choice.

Stay here and be killed.

Or try to get over the fence, topped with bundles of razor wire?

Joshua Jenkins, 33. S.C. Department of Corrections/Provided

Some fight. Others climb. About 20 men scale the fence while attackers slash and hack at their backs and legs.

An inmate sees Joshua Jenkins, a bulky man at 220 pounds, get stabbed and fall like a building at demolition. He watches Raymond Scott get stabbed over and over. They used to play basketball together at another prison.

Corey Scott, 38. S.C. Department of Corrections/Provided

Scott’s close friend, who’s also wounded, rounds the bundles of razor wire. It slices his skin until he leaps and lands in the soggy grass. He, too, watches Scott. Tears blur his vision and stream down his face.

The attackers spit at him, yelling insults.

Nearby, another man shatters his heel and breaks his ankle landing on the ground. Another gets his leg caught up in the razor wire. His leg breaks. As he hangs there, inmates stab him through the fence.

Men scream for help. They shriek for the attackers to stop. Their cries echo across the yard.

As officers retreat to safety, one calls over the radio that inmates have breached a fence. But it isn’t obvious which one. The fence around F-5? The fence to the nearby Prison Industries building? It's not clear the men are fleeing for their lives.

Under stadium lights, the wounded trudge over the open yard toward the front plaza gate, unsure who will help them.

An inmate outside the F-5 gate.

Behind them, not everyone makes it over the fence.

Crumpled under darkness, rain and wind, four men lie on the blood-soaked sidewalk.

Rashawn Carter, six weeks into his sentence, is the only who will survive. He is stabbed in the head, shoulder and arms. Someone hacks him in the leg.

Raymond Scott and Joshua Jenkins lie next to him, along with Corey Scott, who is shirtless and bleeding. As Corey rolls in the mud, gasping for air, an inmate cuts his throat.

Jenkins suffers 60 stab and slash wounds. Tattoos on his hands read: RIP.

Some men who made it over the fence sprint to another dorm up near the prison’s administration building. They bang on the locked front door of F-1 with hands bloodied by razor wire and holler: “They killed Twin!”

From inside the building, men peering down the yard through narrow windows to see inmates lying on the sidewalk near outside F-5. Updates on the violence spread through the thin walls between cells and the air vents above the toilets in each of the rooms. Texts and calls pour in.

Some hear that Crips in F-5 just made the Bloods climb the razor-wire fence.

Now the Bloods in their dorm rush toward the unit's Crips, clustered upstairs together. The Crips run to their cells.

But Cornelius McClary, a stocky 33-year-old, can’t get back into his. The door is locked. He is outnumbered. After getting stabbed, he stumbles down a staircase and collapses on the floor.

From a nearby cell, another man peers out, looking for a security officer. But he doesn’t see one. The lone staff member in the 256-man dorm has fled to the other wing and locked the door.

Blood bubbles in McClary’s nose and mouth, rising and falling with each breath.

The man watches until it stops.

A view from inside the F-5 dorm overlooking a barbed wire fence at Lee Correctional Institution on Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2019 in Bishopville. Andrew Whitaker/Staff

Leaders of the state Department of Corrections have received updates all night, including McCall, the deputy director of operations who approved the mass transfer five months ago.

After speeding over the 70-mile drive from Columbia, McCall arrives at Lee more than two hours after the violence began. He rushes to the command post set up in the warden’s office and finds chaos there.

Radio calls from officers watching the yard warn that inmates have scaled the F-5 fence. No one is sure if they are running for their lives or threatening the entire prison's security.

Cornelius McClary, 33. S.C. Department of Corrections/Provided

Staff think the officer in F-1, where Cornelius McClary is dying, has been taken hostage. On the unit's security camera, McCall sees a dead man lying on the floor.

McCall watches men dart out of F-5 and stab the bodies on the sidewalk.

Calls pour in. Officers are scared. Regional tactical teams arrive. It’s not clear what is going on where or who is calling the shots.

The 20 or so inmates who went over the fence just before 9:30 p.m. now rush toward the prison’s medical ward.

Behind them, bodies lie in a heap at the fence. When inmates run out to stab them anew, an officer on a roof fires canisters of pepper spray to push them back into the building.

But stiff wind and rain captures the mist, carrying it in the other direction.

The first wounded men reach the plaza gate to the administration building. Officers order them to the ground and emerge to handcuff them before taking them inside to the prison’s emergency room. Inmates help, too. With so many wounded, they run out of wheelchairs and gurneys.

Lee County paramedic Shawn Powers is used to medical calls at the prison, but nothing like what he sees now. Officers and inmates shepherd the wounded, limbs dangling from gurneys and industrial rolling laundry baskets. They are covered in blood, smeared with mud and wet from rain.

The men head toward Lee's emergency room, barely big enough for two or three hospital beds, where paramedics and prison medical crews triage the wounded.

Patient after patient arrives. To Powers, it feels like at least 80 men come and go over the next few hours.

Cook, the inmate worker, helps Lee’s medical staff, restocking supplies when paramedics run low. He helps bandage several dozen men with less severe injuries who are milling in nearby rooms or out in the hallway.

When someone almost slips on blood, Cook swishes a mop over the emergency room floor’s aging teal tiles, now streaked with red. He and another man take turns mopping for hours. The smell of bleach fills the air.

Neighboring counties send ambulances to help rush about two dozen wounded men from the prison. But getting them to area hospitals means giving up more prison officers. The 44 staff on campus when the violence began rapidly dwindle with each ambulance that departs.

Inside Lee's character-based dorm, on the East Yard, inmates watch the officer in their building leave. They are unsupervised. But these are men who are trying to follow the rules. They get up and walk to their cells at precisely 11 p.m., as they are supposed to.

McCall can’t spare any more of Lee's officers. He needs to keep some on site who know the campus well. Instead, as tactical team members arrive, he starts sending them out with inmates to the hospital.

A South Carolina Department of Corrections Rapid Response Team bus at Lee Correctional Institution. Andrew J. Whitaker/ Staff

The various teams, who come from around the region, gather at Lee. A force of more than 100 eventually shows up and assembles in the prison’s visitation room.

Their task is to retake the West Yard.

They are given authority to use deadly force, but it’s not clear to everyone under what circumstances. The various groups haven't trained together. Some haven’t been trained in building-clearing techniques. And some go directly to the yard or other locations — including many who are armed — without proper authorization.

At 11:30 p.m., a group of them enters the first dorm, although the violence inside has long ended.

An hour later, another team enters a second dorm.

Down the yard in F-5, Officer Anderson is still trapped in the control room. Finally, at 1 a.m., she notes that special team members are at the entrance. More than three hours have passed since inmates scaled the fence.

Six hours have passed since Michael Milledge was stabbed in his cell.

About 30 miles away at a Florence hospital, medical crews still try to save his life. But they cannot.

At 2:18 a.m., seven hours after he was stabbed, a doctor pronounces him dead. The first inmate attacked is the last to die.

A chaplain leads prayer over Milledge’s body. Then he prays over the prison staff guarding him, including the officer who watched Rivera’s brutal stabbing.

With seven men dead and dozens injured, the night now marks the deadliest explosion of prison violence in America in 25 years.

At 3:10 a.m., more than eight hours after the violence began, Officer Anderson writes for the first time on her shift: “F5 secured.”

A day later, sunshine has replaced the rain when McCall returns to Lee. The entire prison is on lockdown, as are others across South Carolina.

As he walks through the West Yard buildings, where men peer out from behind locked metal doors, he spots blood still on the floors. He sees where McClary died in F-1 and passes a bloody handprint on the entrance to F-3.

Then he heads to F-5 and stands at the fence, razor wire bundled above him. The sidewalk still looks like a slaughterhouse floor.

The following day, another mass inmate transfer begins. This time, buses with dozens of men rumble away from Lee heading to McCormick. Another group will get sent later to a private prison in Mississippi.

Once again, only one officer is working in F-5's control room.

She notes in the unit’s logbook that one of the pod’s doors won’t close. She has informed a supervisor.

But she's told that, as long as the front door is closed, it’s fine.

Netting that rises 50 feet along the perimeter at Lee Correctional Institution was added after the April 15, 2018 fight to help prevent contraband from getting into the prison. Andrew Whitaker/Staff

EPILOGUE

Nineteen months have passed since the killings.

Loved ones are left to deal with the loss of men who were sons, fathers, brothers, cousins. Only one of the seven who died had a life sentence.

Staff and prisoners who witnessed the horrors remain tormented by memories. At least one inmate who survived tried to hang himself. Others describe bloody bodies that haunt their nightmares. Some fear hits are out on them.

McCall and Warden Aaron Joyner are both gone from the agency. McCall said Corrections Director Bryan Stirling forced him to retire or be fired, telling him only that he'd been in the job too long. Joyner said he retired after being moved to a lower-security prison, essentially a demotion, without cause.

And there still has been no public reckoning for what happened at Lee.

An inmate who was at Lee during the violence on April 15, 2018, describes his experience in a letter to The Post and Courier. Andrew J. Whitaker/ Staff

Not a single charge has been filed. Most of the more than 50 prisoners who are, or were, under investigation for the killings remain in lockups around the state. Several told The Post and Courier that no authorities have come to interview them yet.

The most critical audits of Lee — that warned of dangers before the killings and examined the violence after — have been kept from the public.

Among them is an audit performed two months after the deaths by experts from the Association of State Correctional Administrators.

Their report describes many failures in prison officials' handling of the violence. State officials denied The Post and Courier access to it. The newspaper obtained it elsewhere.

Among the findings: There was a delay in establishing a command post that night. Joyner wasn't properly briefed. It wasn’t clear to all staff that Joyner was commander of the scene and should approve all directives.

No single person managed intelligence information. No one oversaw logistics.

This all contributed to the chaos.

The auditors found additional problems with the agency's actions after the killings. “Documentation of the entire event was poor,” and officials had not compiled “lessons learned” from the violence or their response.

The ASCA team feared the entire prison’s safety was in peril.

Stirling insists his agency did learn many lessons and is making big changes. Among them are new locks in F-5, being installed now as the dorm sits empty.

There is widespread agreement about one thing: South Carolina's prisons still desperately need more manpower to keep the people inside its razor wire safe.

Last fall, Stirling asked the Legislature for $6 million to give the agency's officers and other staff $1,000 raises, a measure he said was needed to stop turnover and boost hiring.

Lawmakers denied them that pay hike.

Today, the level of front-line security staff at Lee remains virtually unchanged, with officers as outnumbered as they were when the killing spree began.