(or “OK, WHOIS, but apart from that?”)

Every domain name has so-called “social” information associated with it. It consists for example of the holder’s name, the registrar, the contact persons’ email addresses, the date of creation, etc. This social information is distinct from the more technical information found in the DNS (Domain Name System)1. The information is partly public and can be obtained by any curious user , be it a lawyer preparing an action against the domain holder, a journalist writing an article, a person wishing to report a technical problem or simply an interested third party.

“I don’t have time to read it all”

If you’re in a hurry, not interested in technical details and only need to do this sort of thing from time to time but want information on a domain name, here are two simple ways I recommend trying in this order:

- With a Web browser, go to https://lookup.icann.org/ and enter the domain name,

- If that doesn’t work, and it returns a more or less clear message of the “TLD_NOT_SUPPORTED” type, then go to https://www.iana.org/domains/root/db and select the top-level domain concerned, go to its registry’s website and search.

The rest of this article explains the details.

“Who is...?”

If you ask people who’ve already done some digital investigation, they’ll often tell you “you have to use WHOIS.” The term has a precise technical meaning, but nowadays it is often used quite wrongly to refer to very different things. If I type “whois bortzmeyer.fr” into a search engine, as many people do, then quite apart from the problems inherent in the mere fact of using a search engine2, you’ll generally be taken to a page managed by goodness knows who purporting to present the result of a “whois search”. I’ve just tried it, and the website in question is in indeed that of a non-authoritative actor (neither the registry of .fr nor the registrar of this domain3) giving information about which it is impossible to know whether or not it has been altered4. This kind of “digital investigation” is thus worthless; and yet we sometimes see, for example in the media, a simple screenshot with no indication of where it comes from5, purporting to be a reliable source. The state of digital investigation is such that these screenshots are sometimes accepted as pertinent, whereas they should be rejected.

So, what should we do?

To get better results, we need to keep in mind some important principles:

- We want an authoritative source, not hearsay6. So we’re talking about a database managed by the relevant registry (Afnic for the .fr TLD) or by the registrar with whom the domain name is registered; these sources are authoritative since domain names and the associated information are managed by the holders with these two actors.

- We want to recover this information using a process that can be replicated and documented, for example if we want to present it to a third party or to the public.

- Sometimes a manual process is preferred, but other times we have several searches to carry out, perhaps in a complex work process, and we want to automate.

We will first deal with the case where the person investigating is not a computer expert and is unwilling or unable to automate the search. Newcomers to digital investigation often ask questions such as “Is it easy to do a WHOIS search?” The answer is that the search itself is relatively easy, but interpreting the results can be anything but, particularly in view of the complexity of the world of domain names. For example, the holder of the domain names one.bortzmeyer.fr and two.bortzmeyer.fr is one and the same, but those of one.gouv.fr and two.gouv.fr are different (same thing with one.ac.jp and two.ac.jp). Another frequent trap is the fact that social information is sometimes stored with the registry and sometimes with the registrar.

We’d like things to be simple7 but they never are. If you want to be serious about digital investigation, there are a number of things you have to learn (presented in the section “Things to know”, further on).

One possible approach

Let’s get back to names. Take doq.bortzmeyer.fr (a name that actually exists). Who is the holder? Who is the registrar? How do we reach the technical contact person? It’s a .fr name, so the registry for .fr must know and must be authoritative. So let’s visit its search page (Figure 1). Here we find the registrar, information such as the date of creation of bortzmeyer.fr, the parent domain of doq.bortzmeyer.fr which we were looking for.

Also, you won’t see the holder’s name: this is because, in application of the French Data Protection Act, Afnic has for many years not shown8 the names and contact details of natural persons9(“restricted publication”). In general terms, the registry (or sometimes the registrar) decides what will and will not be disclosed10. For example, the registry of the .de TLD publishes very little information on domain name holders and contact persons.

But just a minute – I used Afnic’s website because it is the registry for .fr and is authoritative for names in .fr. But how do I know where to look if I didn’t know this? The easiest way is to go to the IANA website 11, which lists all the websites for top-level domains.

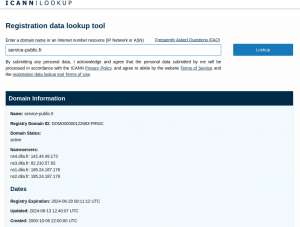

Another, more automated solution is to use https://lookup.icann.org/ is to use (figure 2), which automatically takes you to the right place and thus works for all suffixes.

Things to know

As we said before, the world of domain names is complex. So we need to learn a few concepts and terms.

A domain name is a series of labels separated by a dot. For example, www.forcesarmees.gouv.sn is a domain name with four labels. The most general label is called the top-level domain or TLD. forcesarmees.gouv.sn is a sub-domain of gouv.sn, which is itself a sub-domain of .sn. Names are created by the registry that manages this TLD. Not all registries are accessible to the public. For example most readers of this article will not have the right to create a name under gouv.sn. There are a number of “public suffixes”12 under which people can register names.

Registration is often not done directly but through a registrar. In most cases, the social data (name of holder and contact persons, their contact details) are stored by the registry in its database (“thick registry”). But there are also some “thin” registries, the best known being that of the .com TLD where social data are stored by the registrar. Some of this information, such as the date of the last modification, is in both databases, that of the registry and that of the registrar. There are cases, sometimes seen in legal procedures involving a registry, for example, where the information in the two databases is not the same. There have also been cases of unscrupulous intermediaries having a database that was deliberately different from that of the registry, to hide the fact that the registration had been made in their name.

Registries’ and registrars’ databases can be accessed in various ways. The classic way is the Web, which we used in the two examples above.

Talking of the Internet, time for a little technical explanation: the Internet relies on a number of protocols, which are rules that machines have to follow to be able to communicate with each other. The best known of these protocols is HTTP, used by the Web. But there are others, two of which are particularly relevant to this article: WHOIS13 and RDAP14. These two protocols (three, if we count the Web) are technically different and the choice will depend on the user:

- The Web is certainly the simplest solution, but you need to know the registry responsible.

- WHOIS has some serious technical limitations but the tools that exist partly mask them, plus it has the advantage of being long-established and well-known.

- RDAP is the best suited to automation, and is the one preferred by programmers.

They all give the same information, of course, from the same database15. Note that there are other criteria for choosing among the three techniques presented above. For example, WHOIS has until now been mandatory for TLDs under contract with ICANN, but from 28 January 2025 this will no longer be the case. RDAP is mandatory in the case of a contract with ICANN, but there are certain national TLDs, such as .de in which it is not deployed.

These three techniques for obtaining the social information associated with a domain name are sometimes grouped under the name RDDS, Registration Data Directory Services, but this term seems to be little used in practice.

As we mentioned earlier, the number of labels of a domain name varies greatly. In principle, whether there are two or three labels or more has no significance. For example, u-paris.fr and pasteur.fr are two domains managed by different organisations. But in Japan, universities’ domain names have three labels, like hiroshima-u.ac.jp and osaka-u.ac.jp. How can we tell where the domain reserved with a registry starts? There’s nothing to indicate it in the name. The surest way at present is to look at the Public Suffix List which, although unofficial, is kept fairly well updated16.

The tools

As for the Web, that’s easy – practically everyone has a Web browser and knows how to use it. Note that the RDAP protocol was designed to be integrated with Web technologies, and that a service such as https://lookup.icann.org/ in fact works with RDAP17.

The main difficulty when we use the Web is in finding a website that is both pertinent and authoritative. For TLDs, we can use the IANA page referred to above18. In the case of a “thin” registry such as .com, where we have to find the registrar’s website, using https://lookup.icann.org/ is doubtless the simplest solution.

Having come this far, one important point: if you’re just an occasional user, you can stop here. Because we’re now going to get into some more complex details.

WHOIS poses a problem: as with the Web, you have to indicate the authoritative server; the protocol does not allow you to discover it by default. That said, in practice, the vast majority of WHOIS clients have a mechanism for finding this server19, and for following any redirections, for example from a thin registry to a registrar.

RDAP doesn’t have this problem; the automatic server discovery mechanism is standardised and the user doesn’t have to worry about it.

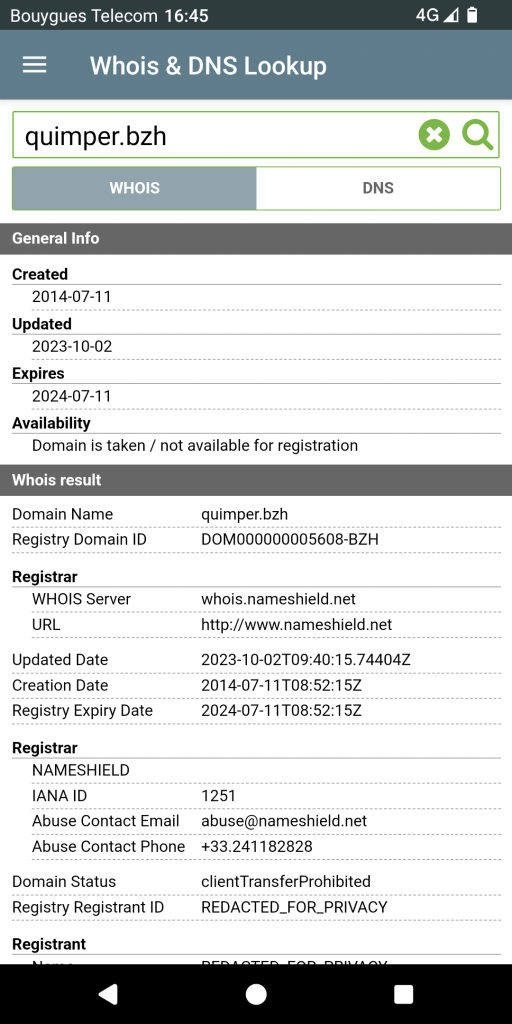

Using WHOIS and RDAP will obviously depend on the platform you work on. You can install RDAP extensions on your browser, thus avoiding having to go to websites such as lookup.icann.org. Let’s start with Android on a smartphone. There are several apps, one of which, for WHOIS, is “Whois & DNS Lookup – Domain/IP”, which has the advantage of also allowing DNS requests (although they will not be used here). The screenshot (Figure 3) gives you an idea of its capabilities.

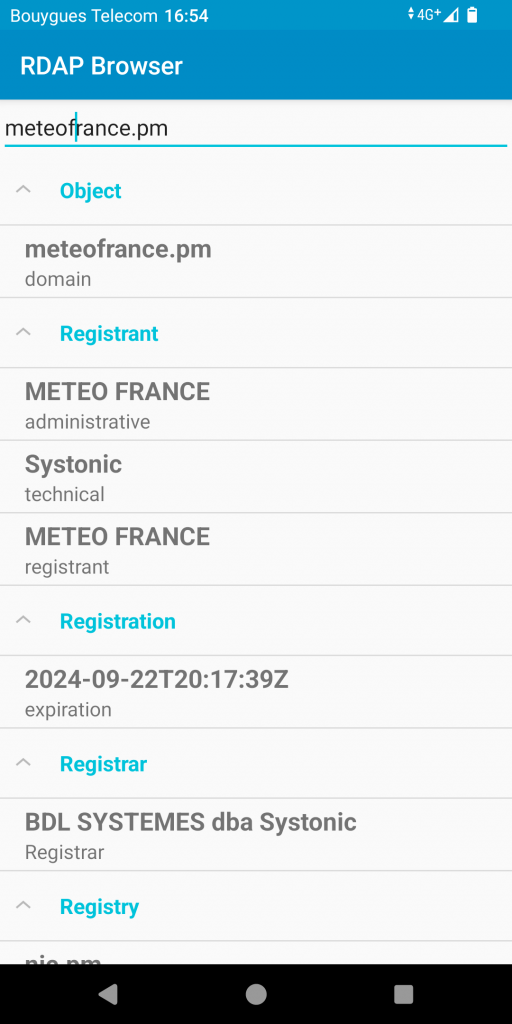

And in the case of RDAP? There is an app developed by the Canadian company Viagénie, which has contributed greatly to the Internet, the RDAP Browser app (Figure 4).

However, I don’t have any information on WHOIS or RDAP customers using Apple’s iOS. If anyone has ideas, please let me know.

And Microsoft Windows? There are several solutions:

- The graphic app WhoisThisDomain.

- Microsoft has a whois command line20 utility.

- A better solution perhaps is to install a Unix-type environment in Windows, for example Ubuntu.

- And for RDAP? You should be able to manage thanks to PowerShell with

Invoke-RestMethod https://rdap.nic.fr/domain/service-public.fr. The resulting document, in JSON format, is automatically decoded and transformed into a PowerShell object, which allows you, for example, to list all the entities associated with the domain, usingInvoke-RestMethod: https://rdap.nic.fr/domain/service-public.fr | Select-Object -ExpandProperty entities.

With Unix, the whois command line utility is normally used. Here’s an example:

% whois chateaunantes.fr

…

domain: chateaunantes.fr

status: ACTIVE

…

holder-c: LVAN20-FRNIC

…

registrar: GANDI

Expiry Date: 2025-03-29T08:27:31Z

created: 2005-09-02T12:04:17Z

…

nic-hdl: LVAN20-FRNIC

type: ORGANIZATION

contact: LE VOYAGE A NANTES

address: 1-3 rue Crucy

address: 44000 NANTES

country: FR

The WHOIS client is capable of following any redirections.

For RDAP, we can use the nicinfo app:

% nicinfo chateaunantes.fr

…

1= chateaunantes.fr ( DOM000000600543-FRNIC )

|--- 1= LE VOYAGE A NANTES ( LVAN20-FRNIC )

…

Domain Name: chateaunantes.fr

Status: Client Transfer Prohibited

Registration: Fri, 02 Sep 2005 12:04:17 -0000

Expiration: Sat, 29 Mar 2025 08:27:31 -0000

Last Changed: Sat, 16 Mar 2024 09:15:26 -0000

Transfer: Thu, 29 Mar 2018 08:27:31 -0000

[ ENTITY ]

Handle: LVAN20-FRNIC

Common Name: LE VOYAGE A NANTES

Organization: LE VOYAGE A NANTES

Email: informatique@lvan.fr

But since RDAP relies on Web-based technologies, such as HTTPS and JSON, we can also use generalist tools such as curl and jq:

% curl -s https://rdap.nic.fr/domain/chateaunantes.fr | jq .events

[

{

"eventAction": "registration",

"eventDate": "2005-09-02T12:04:17Z"

},

{

"eventAction": "expiration",

"eventDate": "2025-03-29T08:27:31Z"

},

{

"eventAction": "last changed",

"eventDate": "2024-03-16T09:15:26.096146Z"

},

…

1 – The techniques presented here also work for IP address registries, but here we’ll be focusing on domain names.

2 – No guarantee of getting a serious response; response changes from one day to the next whenever the algorithm changes; power given to the company that manages the search engine, etc.

3 – In my case, the page I was taken to said the registrar was Afnic, which is in fact the registry.

4 – Or indeed obsolete and out of date if the intermediary in question memorises old responses for reasons of performance, but without making sure they’re updated.

5 – In many cases, the page’s URL is not even visible on the screenshot.

6 – The more so as the Internet nowadays is full of approximate or false content, written by humans or AI for the sole purpose of boosting SEO.

7 – The complexity of the world of domain names is due to many factors, which we do not have time to list here.

8 – By default. But the holder can change this via the registrar.

9 – Contrary to what we sometimes read, this protection does not date from the GDPR (EU General Data Protection Regulation), it pre-dates it.

10 – Although in some cases, such as that of .fr, the holder can influence this decision.

11 – Internet Assigned Numbers Authority, a department of ICANN.

12 – The term, while time-honoured, is not entirely accurate since some of these suffixes are not accessible to the public.

13 – “WHOIS” in fact designates a specific protocol, which is not the only one that can be used. But, not entirely accurately, it is often used to refer to any mechanism for accessing a registry’s database. Similarly, you sometime see the term “port 43”, which comes from a technical characteristic of the protocol and as such means little to the average user.

14 – Registration Data Access Protocol

15 – We sometimes still see the obsolete term “WHOIS database”, which is now meaningless as the database has no connection with WHOIS.

16 – We can round out this method by reading the registration policies set out by each registry for its naming zone, which can be found on the registries’ websites. These documents are sometimes long and difficult to follow, but they’re essential if we want to have all the details.

17 – The same applies to https://client.rdap.org/, except that this does not benefit from an “official” ICANN service.

18 – A frequent but by no means universal convention is to call the domain of a TLD registry nic.TLD. So, for example, in the case of .fr, nic.fr will take you to the registry’s website. Note that this does not always work and that nic.com is not at all the website of the registry of .com.

19 – Although this mechanism is sometimes found wanting when there are changes, as we saw in 2023 with .ga, for example.

20 – Among its limitations is the fact that it does not allow a WHOIS server to be explicitly indicated.