Editorials

‘The Lodge’ is a Dark and Guilt-Ridden Christmas Story [Formative Fears]

Formative Fears is a column that explores how horror scared us from an early age, or how the genre contextualizes youthful phobias and trauma. From memories of things that went bump in the night, to adolescent anxieties made real through the use of monsters and mayhem, this series expresses what it felt like to be a frightened child – and what still scares us well into adulthood.

The events of The Lodge have stayed with me since my first viewing. I remember my gasps becoming more and more audible as terrible things continued happening on screen, and by the end of the movie, I was absolutely drained. There is a lot to unwrap and examine when considering something like The Lodge – not everyone will connect with the cheerless script written by Sergio Casci and later revised by directors Veronika Franz and Severin Fiala. And any chance of surface entertainment is impossible because the story sees no joy nor does it show a modicum of kindness towards its characters and their plight. After watching, viewers will hurry to shake off the movie’s misery and question what exactly was the purpose of it all. From my standpoint, though, the tragedy that befell the Hall family cuts to the heart so deeply, making me think of my own harmful history with self-blame.

The family at the core of The Lodge is carrying on with life as best they can after suffering a horrible loss; Richard Hall’s (Richard Armitage) son and daughter are still mourning their mother’s passing six months later. This year’s Christmas doesn’t feel worth celebrating, but the patriarch has already planned a winter getaway for him, his children, and his new love, Grace (Riley Keough). There’s some understandable pushback and the tension is obvious, but the father doesn’t give Aidan (Jaeden Martell) and Mia (Lia McHugh) much of a choice. Once at the family lodge, Richard leaves for a work obligation; he entrusts his kids in Grace’s care so they can get to know her better. It’s going as well as can be expected until they all wake up to a cold and empty house — everyone’s belongings, the food, Grace’s dog, and the decorations are all gone. The situation becomes even more dire when everyone questions whether or not something unearthly is behind all of this.

We tend to think there’s something wrong with us if we’re not happy around the holidays. In a season of inescapable mirth, you’re at risk of being labeled a “scrooge” if you feel anything but merry at Christmas. Yet for the Hall children, their despondency is justified. Mia fears her mother won’t make it into Heaven, and Aidan looks after his sister so much, he might be neglecting his own needs. While it is sad, this is all customary given the state of things. What isn’t normal is the father feigning cheer when there isn’t any for anyone other than himself; he’s resigned from feeling too upset about Laura’s (Alicia Silverstone) death because he moved on before their divorce was ever finalized.

Richard essentially imprisoning his children in a remote, snowbound house with Grace is what triggers the horrifying events to come. The vacation is not easy for Keough’s character either since the abundance of religious iconography in the lodge stirs up painful memories of her severe upbringing. In fact, that’s how she and Richard met — he was studying the extremist Christian cult that Grace once belonged to before the other members died from mass suicide. Although the children don’t hide their hostility towards her, Grace makes an effort; she wants to be there for them at such a sensitive time in their lives.

Grace is eventually left on her own to care for Aidan and Mia as if her maternal skills are being put to the test. She seems to be making progress with them when she wakes up to find all of her stuff gone — including her medication. The children, who claim they’re not playing a prank, insinuate there’s a greater force at work here. Grace soon succumbs to withdrawal symptoms and paranoia; she worries everything happening is divine retribution for her “sins.” This is where the movie takes an irrevocably dark turn that wasn’t in the original script; Franz and Fiala reach a point of no return. The crushing trauma Grace harbors inside of her starts to manifest as acts of self-harm, and in spite of what she’s told, she sincerely believes everything is her fault and only she can set things right. How exactly she does that is where The Lodge earns its divisive reactions.

Having grown up around shame, I identify with someone like Grace. Whether it was my physical appearance or my inability to smile through my depression, the people in my life were always sure to tell me what I was doing wrong rather than what I was doing right. While I didn’t have the obstacle of religion to contend with like Grace, I still felt secondhand guilt when I began to question my own identity at a later age. As with Grace, I temporarily escaped what ailed me; this was as close to normal as I had ever felt. Grace is ultimately pulled back into that darkness, and there’s no chance of retreating this time. She viscerally remembers the judgment that painted her childhood, and just as she was taught, Grace suspects she’s to blame for all that’s gone wrong. We know she’s been tricked into this mindset, but it’s difficult to undo that kind of learned self-condemnation.

Where Grace and I do differ is important. For she is certain she’s getting what she deserves, but I’m slowly accepting that I didn’t cause my family’s problems like I was led to believe; others are responsible for their own actions. Grace, unfortunately, is so arrested by her father’s harmful teachings and false truths that she can’t help but revert to that way of thinking when everything turns upside down. Putting the blame on herself is easier than Grace admitting her father is toxic and that the way she was raised is not right.

The Lodge is an agonizing and upsetting Christmas movie that people will have trouble watching, much less revisiting. Even so, we can at least acknowledge dark Christmas stories are as important as the feel-good ones. Particularly horror movies that have a strong grasp of the indifference and alienation that so many people feel around this unusual time of year.

Editorials

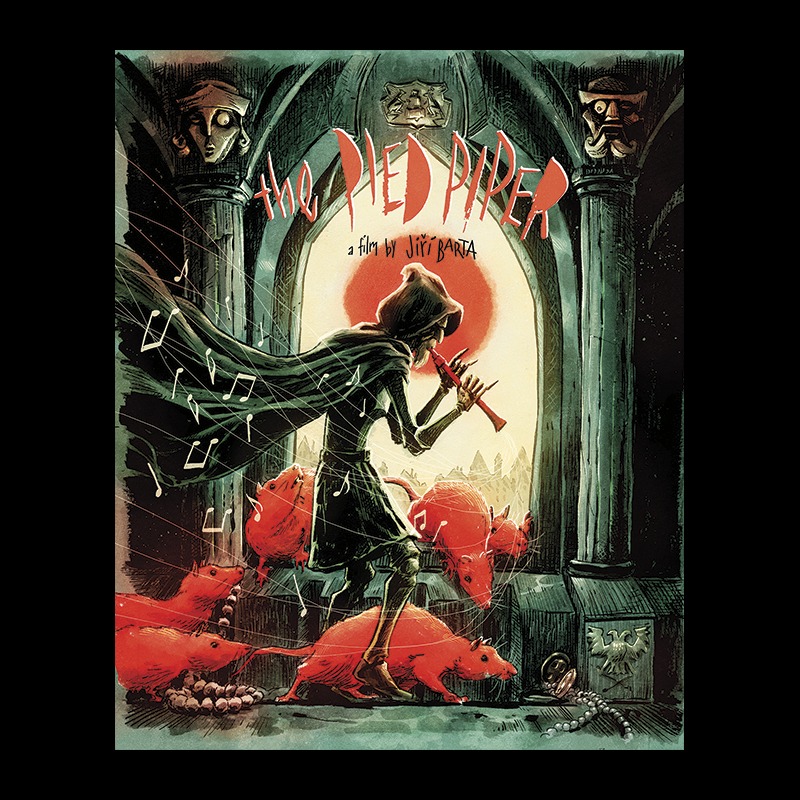

Looking Back on the Stop-Motion Nightmare of 1986’s ‘The Pied Piper’

Genre classifications tend to fall apart the further we look back in time. That’s why nearly all the original versions of classic fairy tales contain at least one bizarrely horrific element or another. From the Evil Queen’s cannibalistic intentions in Snow White to the Big Bad Wolf successfully devouring both granny and Little Red Riding Hood, even the most innocent stories featured a twinge of terror back when they were first created. However, there is one fairy tale that remains surprisingly dark even in its current iteration, and that would be the chronicle of The Pied Piper of Hamelin.

A simple yet memorable yarn about a pipe-playing stranger who takes revenge on the populace of medieval Hamelin once they fail to pay him for eliminating their rat problem, the story of the Pied Piper has influenced countless other works of art (even popping up as a recurring influence on the Slenderman mythos). That’s why I find it so surprising that there’s no definitive big-screen adaptation of the iconic story – unless you count stop-motion animation.

Enter Czech filmmaker Jiří Barta, a pioneer stop-motion animator working for Kratky Film in the early ’80s. Having already made a name for himself by contributing to a myriad of televised short films aimed at children, Barta and the humble studio wanted to branch out and create a large-scale project meant for older audiences. After some discussion, the director settled on a bold retelling of the Piped Piper, wanting to present the story in a way that would stay true to its Germanic roots while also taking inspiration from Viktor Dyk’s 1911 reinterpretation of the tale, Krysař (Rat-Catcher in Czech).

And so production began on a one-of-a-kind animated spectacle that would incorporate German expressionism and medieval artwork into its visual design. Over the course of a year, Kratky’s artists produced meticulously crafted puppets and locations meant to evoke wood carvings – as well as a rat infestation brought to life through taxidermized skins and the occasional use of live-action photography.

Not very appetizing.

In the finished film (which doesn’t require subtitles since the characters all speak in a fictional German dialect that we aren’t meant to understand), we follow the downfall of Hamelin as the wealthy townsfolk become corrupt in their miserly ways, with the bustling city eventually attracting a vicious swarm of rats. It’s only then that a pipe-playing stranger comes to town and is promptly hired to take care of the problem. Naturally, the Piper is soon betrayed, leading to a horrific comeuppance as the town faces the consequences of extreme avarice.

In 1986, Krysař (retitled to The Pied Piper in North America) would premiere to rave reviews, though this success remained mostly limited to the festival circuit and Eastern European theaters. It would actually take decades for the film to reach home video in America, with most Western cinephiles only coming across this landmark stop-motion fable through bootleg copies and international DVDs aided by the film’s lack of intelligible dialogue.

This aura of mystery may be partly responsible for the film’s enduring legacy as an obscure cult movie, with fans considering it one of the greatest hidden gems of all time, but it’s The Pied Piper’s exceedingly dark tone and imagery that really cemented its place as a classic.

While the general plot was faithfully recreated from familiar versions of the story, which is already one of the darkest fairy tales in existence (possibly due to its origins as an allegedly true horror story), it’s the flick’s deviations from its folkloric source material and the clear preference for Dyk’s bleak retelling that make it such a memorable experience.

For starters, the animated visuals actively enhance the story’s surreal undertones, making a serious experience that much more unsettling due to its whimsical presentation. Horrific moments like the murder and implied sexual assault of a sympathetic main character become downright disturbing when told through the eyes of wooden puppets, and the clockwork-inspired movements of the city folk reveal sinister implications about the inner workings of an oppressive metropolis.

“Them filthy rodents are still coming for your souls!”

The rat plague itself is also incredibly unnerving, with the rodents’ organic design intentionally clashing with the mechanical feel of the rest of the film. The director originally intended for the vermin to feel more alive and sympathetic than the jaded inhabitants of Hamelin, but the use of real rat taxidermy also adds an additional layer of uncanny terror to the mix as the furry plague invades a mostly sterile production.

Of course, the scariest addition to Barta’s The Pied Piper comes from its grisly ending, which ditches the traditional climax of having the Piper kidnapping the local children and instead goes down an unexpected route of city-wide body-horror. I won’t spoil the details for those who still haven’t seen this wood-carved masterpiece, but suffice to say that the finale will stay with you long after the credits roll.

Like the legend that inspired it, The Pied Piper is much more than just a horror story. It’s an anthropological cautionary tale. It’s also a tragic love story, as well as a cathartic revenge yarn. But regardless of how you interpret it, it’s the overall brutality of Krysař that makes it so unique. That’s why I’m glad that the folks over at Deaf Crocodile have finally given the film the remastered Blu-ray release that it desperately needed.

And in a world where adult-oriented animation is finally getting the attention it deserves, with filmmakers like Guillermo del Toro championing the cinematic format as a medium rather than a genre, I think it’s worth looking back on Barta’s magnum opus as a poignant reminder that nightmares are not limited to live-action.

You must be logged in to post a comment.