The Sunflower and the Soul: Wendell Berry on the Collaborative Nature of the Universe and the Cure for Conflict

By Maria Popova

“Every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you,” Walt Whitman wrote an epoch before the Nobel-winning physicist Erwin Schrödinger examined the quantum conditions of existence to ask that urgent, discomposing question: “What justifies you in obstinately discovering… the difference between you and someone else… when objectively what is there is the same?”

It is not simply that we are here, made of the same matter, sharing the same improbable planet; it is that the sharing makes us what we are, each of us a fractal of this immense and indivisible ecosystem of relationship, a golden strand in a tapestry whose only meaning is in the interweaving of its threads.

That despite this elemental interdependence we remain riven by conflict and division is the great paradox and the great tragedy and great opportunity for redemption.

In his agrarian essay collection The Art of the Commonplace (public library), poet, farmer, and philosopher Wendell Berry dismantles the paradox to the building blocks of the tragedy and reconfigures them into a cathedral of redemption.

In what is nothing less than an act of countercultural courage and resistance, Berry indicts the Western capitalist mythos of “self-fulfillment” as the root of this artificial and often violent erasure of our interconnectedness and considers its fundamental logical flaw:

The problem, of course, is that we are not the authors of ourselves. That we are not is a religious perception, but it is also a biological and a social one. Each of us has had many authors, and each of us is engaged, for better or worse, in that same authorship. We could say that the human race is a great coauthorship in which we are collaborating with God and nature in the making of ourselves and one another. From this there is no escape. We may collaborate either well or poorly, or we may refuse to collaborate, but even to refuse to collaborate is to exert an influence and to affect the quality of the product. This is only a way of saying that by ourselves we have no meaning and no dignity; by ourselves we are outside the human definition, outside our identity.

To illustrate how erroneous this notion of an individual separate from relationships is, Berry recounts visiting the experimental plots at the Land Institute in Salina, Kansas, and being pointed to a huge Maximilian sunflower growing alone and apart from other plants. The man who had planted it proudly held it up as an example of a plant that has “realized its full potential as an individual.” Berry counters:

Clearly it had: It had grown very tall; it had put out many long branches heavily laden with blossoms — and the branches had broken off, for they had grown too long and too heavy. The plant had indeed realized its full potential as an individual, but it had failed as a Maximilian sunflower. We could say that its full potential as an individual was this failure. It had failed because it had lived outside an important part of its definition, which consists of both its individuality and its community. A part of its properly realizable potential lay in its community, not in itself.

In a sentiment springing from the same defiant recognition that led Albert Camus to refuse the choice of right side and wrong side in conflict, Berry adds:

To make conflict — the so-called “jungle law” — the basis of social or economic doctrine is extremely dangerous. A part of our definition is our common ground, and a part of it is sharing and mutually enjoying our common ground. Undoubtedly, also, since we are humans, a part of our definition is a recurring contest over the common ground: Who shall describe its boundaries, occupy it, use it, or own it? But such contests obviously can be carried too far, so that they become destructive both of the commonality of the common ground and of the ground itself.

Echoing Schrödinger’s quantum-lensed koan-like insight that “this life of yours which you are living is not merely a piece of the entire existence, but is in a certain sense the whole,” Berry writes:

The business of humanity is undoubtedly survival in this complex sense — a necessary, difficult, and entirely fascinating job of work. We have in us deeply planted instructions — personal, cultural, and natural — to survive, and we do not need much experience to inform us that we cannot survive alone. The smallest possible “survival unit,” indeed, appears to be the universe… Inside it, everything happens in concert; not a breath is drawn but by the grace of an inconceivable series of vital connections joining an inconceivable multiplicity of created things in an inconceivable unity. But of course it is preposterous for a mere individual human to espouse the universe — a possibility that is purely mental, and productive of nothing but talk. On the other hand, it may be that our marriages, kinships, friendships, neighborhoods, and all our forms and acts of homemaking are the rites by which we solemnize and enact our union with the universe… They give the word “love” its only chance to mean, for only they can give it a history, a community, and a place. Only in such ways can love become flesh and do its worldly work.

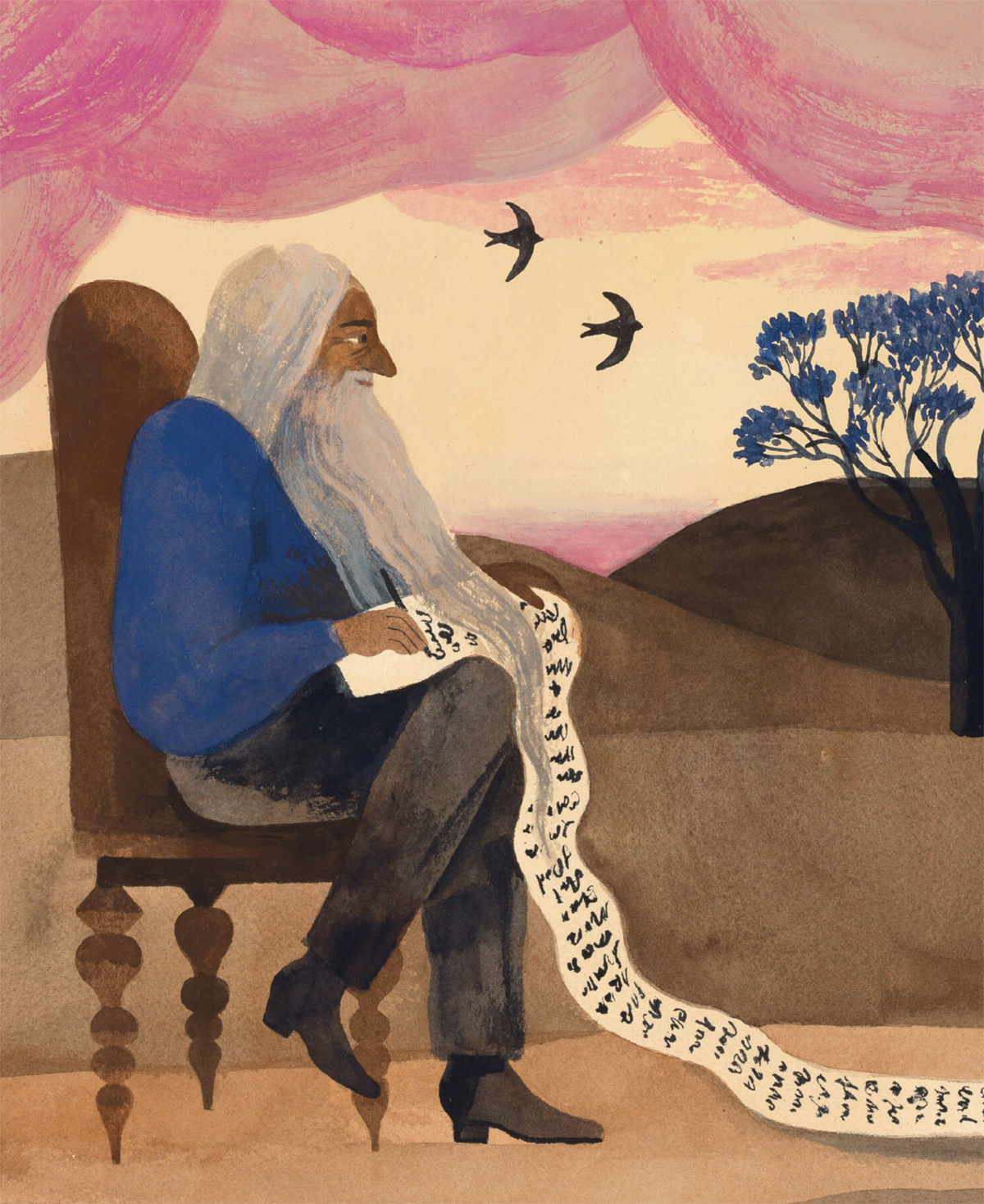

In consonance with the Nobel-winning poet and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore’s insistence that “relationship is the fundamental truth of this world,” Berry adds:

It is only in these bonds that our individuality has a use and a worth; it is only to the people who know us, love us, and depend on us that we are indispensable as the persons we uniquely are… Separate from the relationships, there is nobody to be known.

Couple with Rachel Carson on wonder — that ultimate gasp at the interrelations of things — as the antidote to our human folly, then revisit Berry on the key to mirth under hardship, the peace of wild things, and how to be a poet and a complete human being.

—

Published July 1, 2024

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2024/07/01/wendell-berry-sunflower/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr